Chapter 49: War's Evils

The Champ de Mars, Montreal, April 2nd, 1863

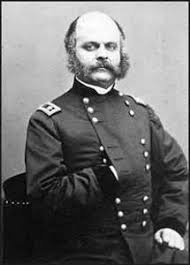

Macdonald watched with some dissatisfaction as the two men were led out by their comrades. A large crowd had gathered, and he felt distinctly at unease. Though he sensed less hostility, and more curiosity. Beside him stood Cartier, Lysons, and Tache. Both the soldiers looked resplendent in their well polished dress uniforms, and the city fathers looked no less so. Mayor Jean-Louis Beaudry in full regalia, Bishop Bourget, John Redpath, George Stephen, and even Dorion were attending.

“I still find this distasteful.” He said, taking another nip from his flask. “I saw enough fools killed in 1838. Well meaning fools, but fools all the same. Shooting them seems like such a spectacle.”

“The men who occupied Windmill Point were hardly serving in Her Majesties forces.” Lysons said. “Those American bandits got what they deserved, and we cannot do anything but treat the mutineers here the same way. It is the law, military law, and we must maintain discipline, especially in these times, hangings would do no good here.”

“I relish this no more than you Monsieur Macdonald.” Tache added. “I treated with them myself, but I never promised them all amnesty. Besides, on the terms agreed the 36th Battalion was disbanded, and such a step must be heralded by those responsible being held accountable. The trial was held by a Volunteer tribunal, and our men, Canadien men, found them guilty. It is only fitting that we carry out the sentence.” He indicated the posts erected at the end of the parade ground.

The two mutinous captains were led, gently, by soldiers of the 5th Battalion to the posts. A priest accompanied them, and the two were tied without incident. Both men accepted blindfolds, but only one the cigarette. They were given a few moments to confer privately with the priest, before he walked behind the line of men assembling. A captain in the 5th stepped beside his men, sword drawn. Colonel Dyde stepped forward to read the charges to the assembled crowd.

As he did Cartier spoke up.

“I can understand their urge to take up arms.” That earned him narrowed eyes from Tache. “I was young and exuberant myself in ’37. We fought for what we believed was right. I don’t know if those men were wrong to fight, but I have discovered that the violence only begot more violence, and those who live by the sword shall surely die by it.”

“Hence why you’ve hitched your horse with me.” Macdonald smiled. Cartier favored him with a grin.

“We’ve accomplished more via the ballot than was possible with the rifles we had. This Coalition we have created is too important for us to be divided by petty issues over the ballot. We’re fighting for our very survival, and that has already cost lives. These men do a disservice to their home by hindering any defence of it.”

“Quite right sir.” Lysons said. “Though I find the ballot an unseemly process myself, men should not take up arms against their Sovereign. This government has been just, and acted well within the law. Whatever their reasoning, we have handled them gently, more gently than they deserve at any rate.”

Dyde finished his own small speech and stepped back. The militiamen stepped forward.

“Ready!” Cried the captain raising his sword. Macdonald took another sip from the flask.

“Aim!” The rifles rose and men took to knee.

“FIRE!” He chopped his sword forward and the rifles cracked as one. The men on the posts jerked as they were perforated with shot, and then fell limp. A few cries of shock went up from the crowd, but it was soon deathly quiet.

“It is done.” Lysons said. Macdonald shook his head, thinking back to the faces of the men imprisoned in Fort Henry all those years ago, the thunder of the cannons at the Tavern, he thought of the faces of the men lined up for battle just 30 miles to the south. It’s a long way from done, he thought quietly to himself.

Whitehall, London, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, April 4th 1863

“I tell you again it is a weapon!” Gladstone exclaimed emphatically. Palmerston hid a sigh. Gladstone was going on again about an issue he had not been keen to drop since October last. Both Somerset and Russel were nodding with him as he trundled on regarding the merits of the Confederate States.

Palmerston himself however, was thoroughly tired of the rousing arguments being trotted out before the Cabinet. As Gladstone paused for breath he loudly rapped his knuckles on the table.

“Now gentlemen, to business.” He said smiling thinly. Gladstone looked as though he would object, but instead grumbled and took his seat. Soon he would manage to force Palmerston’s hand, but Palmerston would hold that off as long as possible.

“What news from the east?” Palmerston asked gravely.

“The Russians continue their subjugation of Poland, though now they have dispatched men to Lithuania as the uprising there becomes more serious. It seems that the French protests on the part of the Poles has come to naught, and Austria shows no interest in aiding them. Though we’ve rained protests down on the Tsar’s head he has been stonily silent or dismissive of our missives.”

“Any sign of a reaction to the Greek crisis?” Palmerston asked.

“Not as of yet. The Russian army seems completely intent on the crushing of the revolution, they’ve paid little mind to events in Greece it seems. The Polish rising could not be more fortunately timed in that regard. Our show of force in the Ionian Islands should serve to deter any adventurism on their part.”

“This is just as well.” Lewis added. “The secret convention between Prussia and Russia is most distressing. Threatening to combine their arms to crush the Poles, its atrocious. That fellow Bismarck has no shame!”

“If he has no shame should we fear he will goad the Gallic Bull to arms?” Palmerston asked. The specter of war had seemed very real when the Poles had risen in revolt three months ago. Russel shook his head.

“The French and the Austrians have condemned it as we have. I doubt either the Tsar or Prussian King feel they would be strong enough to invite the wrath of all Europe over the Polish question. We shall see how the Emperor in Paris plays his cards, but as he is digging himself deeper in Mexico I will be surprised if he pushes for war this year.”

“This year at least.” Palmerston grumbled. “Though speaking of this year, how has our planning developed over the winter?” Somerset was first to speak, regarding a pile of reports in his hands.

“We have the most recent reports from Admiral Milne just in yesterday from one of our steamers. He reports Cochrane’s ‘Particular Service Squadron’ has been most active in vexing the American coasts. It has bombarded Portsmouth again, and visited destruction on numerous smaller American inlets with fortifications. He believes this will keep the Americans guessing as to our naval intentions, as well as mounting further pressure on the American mob to negotiate.”

“Any further debacles we should be aware of?” Palmerston asked. Somerset bit back a retort and steamed on.

“The American squadrons in action have been in harbor for the winter months. Admiral Farragut’s ships have not bestirred themselves since November, and nor has a single one of our patrols been seriously challenged save by their batteries ashore. It is Milne’s opinion they are husbanding their resources for a push later in the year. Though he regrets to report that the winter months have roughly impacted his vessels serving off New York and Massachusetts.”

“Such is the fair weather of North America.” Gladstone snorted. “I assume he will be sending those ships on home for repair?”

“Naturally.” Somerset said. “He however assures us that none of this will interfere with his proposed operations this spring.”

“I for one remain leery of these operations.” Granville said. Lewis nodded as well. “All the frustrations of Sevastopol might be repeated, why are we to believe that this General Lee will deliver upon his lofty promises?”

“Come now, it is not as though I am proposing we divert troops from the Army of Canada or the Army of New Brunswick to help here.” Palmerston protested. “Milne has been supportive of acting in concert with the Confederate army for over a year now, and our own reports from Fremantle suggest that their army is much improved from the spring. Besides, General Lee led a daring raid into Maryland just this November, with the support of the fleet what might he accomplish now?”

“With two fleets we were vexed by the French in the Crimea.” Lewis recalled acidly. “I too am concerned, but so long as we are not removing men from our own goal we ought to be reasonably certain to avoid bad press if all goes wrong.”

“I am hoping that you gentlemen remember that in 1814 our fleet alone helped burn Washington and threatened Baltimore while sealing up their coast from Maine to New Orleans.” Palmerston said. “Now we will be helping one-hundred thousand Confederates with our fleet, we might end the war in a season! In conjunction with the Army in Canada and our gains in Maine and on the Pacific what hope has Lincoln to fight on?”

“We must hope he will finally see reason.” Granville said. “Why he did not seek terms last fall is beyond me.”

“The American mob must be placated.” Palmerston said dismissively. “He must have something to show so he is not thrown out of office. I have heard his enemies made significant gains last year, and this is sure to startle him. Lincoln and Seward are ever at the mercy of their newspapers and voters, it will drag this war on beyond reason.”

There were nods of agreement around the table. None doubted that the war was driven by the whims of the American populace rather than the proper decision making process exercised by a common sense Parliament. Palmerston himself was quite comfortable in thinking that if the people of the Disunited States desired a harder war he would gladly give it to them.

“The Army in Canada is quite ready for service.” Lewis replied. “Dundas has formally organized the army into three corps-”

“Three corps?” Granville asked.

“Yes, two in Canada East under Paulet and Grant, and Williams has been reassigned to Canada West to command the Third Corps. We have a spare division operating with the army in Canada East, and our reserve division in Halifax under Windham if any trouble should arise in Maine or the Canadas. All told, there are forty-eight thousand men under arms in Canada East ready for the spring campaigning season. All Dundas waits on is the thaw.”

Palmerston made no effort to hide his smile. Nearly fifty-thousand British troops poised like a dagger over the heart of the United States. True there was some fear that the whole expedition might end up like Burgoyne at Saratoga, Palmerston felt no difficulty would be forthcoming. The timid Williams had been dispatched elsewhere, and a hard fighter was leading the army now. They had effectively occupied all of Maine, and were poised to strike a blow at the heart of American industry.

“Then once the thaw arrives, I cheerfully anticipate in a month, two months at most, we shall hear Dundas is establishing his headquarters in Albany. Then, we can hope Lincoln and Seward will come to their senses and seek terms.” Palmerston said. “And with that, victory will be in our grasp.”