There, how will relations with religious fanatics evolve? mystery and gumdrop...

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Californie- French California

- Thread starter The Tai-Pan

- Start date

Glad seeing another chapter, I wonder how a Mormon church that hasn't been through the same exact treatment of OTL will develop

There, how will relations with religious fanatics evolve? mystery and gumdrop...

Laïcité intensifies

Just caught up on this and seconded the Turtledove nomination. I love this TL! Well written, and delightfully "messy". No easy, straight-forward protagonist/antagonist plotline, but a massive multi-car pileup of differing factions, cultures, and agendas. I just keep imagining each new Governeur stepping off the ship after months at sea, looking at the clusterf- he's been handed, and saying, flatly, "Merde."

A real Gumbo here. Great stuff, @The Tai-Pan, and good luck on the Turtledove.

A real Gumbo here. Great stuff, @The Tai-Pan, and good luck on the Turtledove.

Post #18- Redwood Empire

Post #18- Redwood Empire

I like trees because they seem more resigned to the way they have to live than other things do.

Willa Cather

With the possible exception of the most arid interior deserts, the redwood forests of northern Californie were the most isolated areas of the French colony. The Spanish missions and landlords had never ventured this far north, leaving it an unexplored land, let alone an exploited one. The Russian fur trappers had passed through but they had been content to remain at the ocean’s edge, plundering the otters and moving on. A few American and British fur trappers had penetrated the vast forested expanses in search of beaver but they had left little trace. For the Wiyot people who lived here Europeans were a distant rumor, heard of but rarely seen. They still lived as they had always done, hunting and gathering in the vast northern woods, quite alone.

Until Étienne Cabet and his Icarians came in 1850, dropped off by an overworked Moerenhout, eager to be free of at least one distraction. They had been sent without supplies, without guidance and certainly with no promises of further support. Just free transport north, and wide ranging if vague land grants. At first glance, the shore seemed a desolate place to build a colony. The soil was thin and rocky, full of gnarled tree roots. The bay, which they quickly named Cabet Bay, was deep and cold, and high mountains towered over them. Most striking were the woods, a vast impenetrable curtain of greenery made of truly gigantic redwood trees. For people not long removed from temperate France, it seemed a world away. Yet, for those with eyes to see, there was great potential here. For one thing, the looming redwood forests promised a virtually unlimited supply of wood and the deep water was the only such harbor between San Francisco and American-held Oregon. The water teemed with both fish and whales, while the mountains suggested mineral finds for those brave enough to reach them.

The rather imposing shores of Cabet Bay, complete with this grass covered sandbar.

Still, for those first Frenchmen, it seemed an empty, alien land.

Of course, it was not actually empty and before long the Icaraians met the first Wiyot. Out of both personal feelings and blunt necessity Cabet was friendly with the Wiyots, explaining his purpose was to set up a small community near the beach. The Wiyots, puzzled by all of this, simply watched and waited while Cabet and his fellows set about laboriously building a home. They named it L'Esperance, Hope, after an early Cabet publication. Despite quickly building housing, storage and workshops out of the abundant wood, the settlement did not live up to its name.

For one brutal year Cabet stuck to his original plan for creating a communal farming settlement, one of pure self-sufficiency and simplicity. That ideal, of a socialistic utopia of collective farmers nearly spelled the doom of the entire enterprise. Not knowing the local landscape, the Icarians suffered greatly in that first year, struggling to clear the soil and most crops failing anyway. A full third of the would-be settlers abandoned the colony, returning back to San Francisco on one of the irregular visiting French ships. Only the generous spirit of the Wiyots (and the French desperation to trade their few manufactured goods for food) saved L'Esperance from total disaster.

A painting of the leader of the Wiyot's, nicknamed Jean Martin DuBois by the French

The next spring even the stubborn Cabet had to admit that farming, while not impossible in some of the flatter river bottoms, was clearly not how his Icarians would survive in this new environment. In what seems a painfully obvious move they turned to conspicuous wealth all around them. The trees. Timber, sold to San Francisco, was Cabet’s new watchword. Selling timber could provide all the money that his settlement needed to thrive, and not to mention supplying wood for all of their own needs. Cabet’s plans for L'Esperance involved schools and libraries, elaborate town centers and theaters. Perhaps that could all be paid for by lumber instead of produce.

Of course none of the Icaraians were experienced lumberjacks or woodcutters, but they did have the advantage of coming from a nation with a deep and rich history of forest husbandry. Even as Cabet and his utopians struggled and starved in northern Californie, Napoleon III was creating the first nature preserves in the forest of Fontainebleau, protecting them from the hungry axes of the foresters. So with this tradition in mind, Cabet drew up a complex map of forest cuttings and harvesting. Never one to shy away from elaborate plans, Cabet soon had schedules of vast dimensions in both space and time, regulating the careful removal of trees for the next century. With his blueprint in hand, the Frenchmen went forth and began to cut down the forest in earnest.

This sudden change in directions was not lost on the Wiyot people, who missed very little the Eurpoeans did. Their leader, a man the Icarians nicknamed Jean Martin DuBois (of the woods), quickly arrived and inquired about the sudden burst of logging. When Cabet revealed his grand plans, the two soon fell into sharp disagreement. Jean Martin was quite aware that large scale logging would disrupt the local landscape, and adversely affect his people. Still, the French leader did manage to mollify the locals by saying the cutting would be small-scale and, in a rare gesture from a white settler, promised to recompense Wiyot for the loss of their local resources. Assuaged by this arrangement, Jean Martin acquiesced and even offered to help the French, if they were willing to pay.

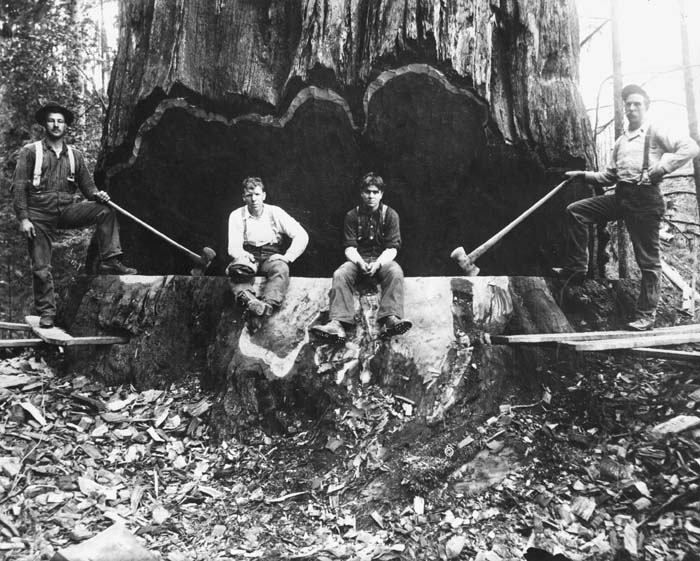

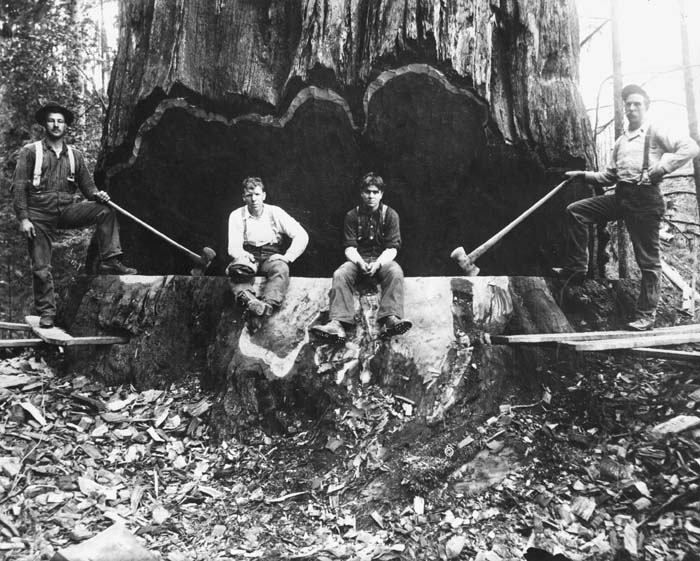

With this agreement, the French turned to the herculean task of actually logging the redwood forest. These massive trees, many of which rose over two hundred feet into the air, sometimes had bases fifteen to twenty feet in diameter. Worse, since the water-logged wood near the stump would not float (the only possible way of moving the enormous logs once felled), the actual cutting had to take place some twenty feet off the forest floor. High platforms had to be cut and wedged into place, to even begin the work of felling. The Icarians had to wield long axes to cut deep into the redwood’s heart, creating a vast undercut notch, many feet deep. This notch was cut, backcut and finally wedged until the huge tree toppled The first loggers who managed to bring a forest giant down found, much to their dismay, that the brittle redwood would often smash into splinters when it hit the ground, spoiling days or weeks of work. The French learned to create ‘beds’ for the trees to fall into, vast trenches lined with branches and leaves. Then, once safely on the ground, the trunk had to be laboriously rolled (often by brute force of dozens of workers) into a nearby river, to be floated down to the crude sawmill near the shore.

A redwood, shortly before felling.

Still, despite the dangers and difficulties, in the year 1852, the Icarians cut down and processed hundreds of massive trees, sent off to a wood hungry San Francisco. With that income L'Esperance could shift from mere survival to actually thriving, and for the first time, Cabet’s unique social vision started to actually take shape. The Icarians lifestyle was to be dominated by communal activities. They lived together, ate together, and worked together. All apartments had the same furniture, the same clothes, and the same dimensions. Children were raised and educated in communal creches, instead of by their parents. A school was built, as well as a small library and a ramshackle ‘concert hall’ where weekend social events were held. One unusual feature of the small hamlet was what was missing. L'Esperance had no church or formal place of worship. Religion played an unusual role in Icarian thought, difficult for outsiders to understand. They believed in a high power who followed the Ten Principles laid out on Cabet’s writings. While strange, the little settlement prospered enough that a few converts from San Francisco wandered in, drawn by stories filtering south along the lumber trade. Gaining new converts was a novel, but gratifying experience for the Icarians, who finally thought utopia was in sight.

The unusual experiment might have gone one in such a vein indefinitely except for new arrivals to the region in 1853.The Americans had finally arrived.

Drawn toward the northern forests by San Francisco’s endless desire for lumber, they had arrived, axes in hand, to strike it rich among the redwoods. Unlike the cautious Icarcians, the new arrivals had no long term plans or other priorities. Their goal was was cutting down trees and they quickly got down to business. Rude logging camps sprung up all throughout Cabet Bay, virtually ignoring Icarian land grants and Wiyot complaints. The utopians and natives alike quickly found themselves helplessly watching a new found industry explode around them.

And explode it did. In 1852 the Icarians, through great labor, had provided roughly 800,000 board feet of lumber for export. In 1854, after two years of busy expansion the Americans had cut down nearly five millions, with a great deal of growth yet to come. Sawmills ran day and night, using huge sawblades over fifty inches in diameter. Heaps of sawdust piled around the camps, clogging rivers and creating impromptu dams across streams. When the easiest trees were felled, the logger headed further inland, importing teams of oxen to drag the massive logs to the waterside for transport. The redwood empire, the increasingly common name for the area, was clearly under construction.

A team of American oxen pulling a massive log. Note the clear cut forest behind.

It was nothing short apocalypse for the Wiyot. Unlike the Icarians, who had at least taken the Native Americans into account before embarking on new projects, the Americans ignored them viewed them as little more than nuisances to be cleared off the land as fast as possible. It did not take long for violence to break out all over the region, with both sides resorting to raids and ambushes. The loggers, better armed and more numerous, often had the best of the Wylot in these encounters. Untroubled by moral niceties, the whites became quite adept at attacking Wylot villages during festivals or events that kept the men away, leaving the elderly and children as easier targets. The fate of those who survived such attacks was bleak as many were forced into slavery, often acting as forced domestic service for the nearly entirely male population. In a few short years the Wylot world was shattered, and their population in steep decline.

Outraged but impotent to all of this, Étienne Cabet reacted poorly to the turn of events. Unable to confront these new arrivals directly, he did little but send increasingly querulous notes to a distant Mohrenhout, complaining about how the Americans were violating his legal rights. The Governor essentially ignored the complaints however, seeing no meaningful issue. San Francisco needed a gargantuan quantity of lumber and having it from Californie itself was the only way to sustain the explosive Gold Rush induced growth. Morhrehout did not care much if they upset a religious fanatic or destroyed some distant landscape. His only minor concern was if these rough and tumble loggers united with their fellow Americans in Oregon, but the lumbermen exhibited no political aims. Unlike the restless Argonauts, these Americans seemed quite content to make it rich.

Ignored, Cabet withdrew and became increasingly tyrannical over what he could control, L'Esperance. The philosopher began to promulgated ever stricter rules of morality for the settlement. Tobacco and alcohol was banned for all, a curfew enacted and leisure time increasingly surveilled. Cabet even went so far as to forbid idle talk in the workshops during the, increasingly mandatory, working hours. To protect these unpopular regulations, Cabet strove to increase his own power, and extended his term of office indefinitely via changes in the town charter. These moves alienated many in the community, dividing the socialist village against itself. The dispute probably would have ruptured the entire project if Cabet had not suddenly died of a heart attack in 1855.

A modern model of Cabet's dream, a perfect utopia.

Freed of his dominating leadership, the Icarians began to more accurately assess their situation. The arrival of the Americans, while a total disaster for the increasingly fragmented Wylot, were only a mixed blessing for the French. While the Americans had, by sheer dint of numbers, wrestled away most of the lumber trade, the utopians still had considerable assets to draw on. Despite American violations they still had expansive land grants, consisting of the finest timber and most of the water courses. They had friendly relations with the Wylot, which provided labor, resources and information. Lastly, as generally middle class artisans they had labor skills the lumbermen lacked.

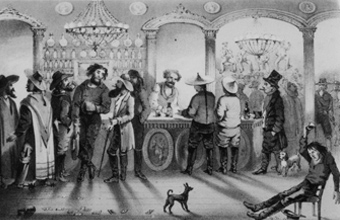

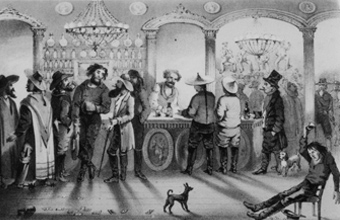

With a flexibility that would have shocked Cabet, had he still be alive, the Icarcians once again changed roles. Instead of lumbering directly, they went after the considerable secondary market opened by the inrush of Americans. The Icarians built the blacksmiths and repair shops the loggers needed, the small farms to feed them, the little factories to make nails and machine belts. Icarians sharpened the sawmill blades and built the wagon wheels for the ox teams. The Frenchmen opened a grocery to serve the hungry logging men. Most importantly, the Icarians began their first tentative forays into boat-building, which would have ramifications for generations to come. The only industry the Icarians did not seize was the entertainment district that blossomed along the waterfront, among the warehouses and quays. Nicknamed the Spanish Quarter, it earned fame throughout Californie as the roughest red-light district in the colony.

The dissolute and diverse Spanish Quarter.

In 1857, thriving as middle-men, the Icarians (now led by an executive committee) finally tried to take action against the loggers. Sending a note to San Francisco, they avoided the whining tone Cabet had used, and did not mention their own rights at all. Instead they raised two other points about the lack of an official French presence in Cabet Bay. First was the immorality on display in the Spanish Quarter, a ‘veritable temple to Mammon’ as their letter put it. Did the French leadership really want such a black stain on their colony’s good name? Secondly they hinted that illegal, unregulated trade was happening there, with lumber being diverted away from Californie and to the growing American cities on the Oregon and Washington coasts.

The response to this carefully written appeal was less than the utopians had hoped. A small detachment of two dozen French marines arrived, as well as a few would-be sheriff deputies. Barely enough to survey the transgressions, let alone meaningfully counter them. Unbeknownst to everyone however, one of the men in the new arrivals would change the fate of the redwood empire forever. An artistic leaning young soldier named Oscar-Claude Monet would, some day, become synonymous with the northern woods for reasons quite beyond anyone’s guess.

A picture of Claude Monet in 1858, as yet, no one of importance.

I like trees because they seem more resigned to the way they have to live than other things do.

Willa Cather

With the possible exception of the most arid interior deserts, the redwood forests of northern Californie were the most isolated areas of the French colony. The Spanish missions and landlords had never ventured this far north, leaving it an unexplored land, let alone an exploited one. The Russian fur trappers had passed through but they had been content to remain at the ocean’s edge, plundering the otters and moving on. A few American and British fur trappers had penetrated the vast forested expanses in search of beaver but they had left little trace. For the Wiyot people who lived here Europeans were a distant rumor, heard of but rarely seen. They still lived as they had always done, hunting and gathering in the vast northern woods, quite alone.

Until Étienne Cabet and his Icarians came in 1850, dropped off by an overworked Moerenhout, eager to be free of at least one distraction. They had been sent without supplies, without guidance and certainly with no promises of further support. Just free transport north, and wide ranging if vague land grants. At first glance, the shore seemed a desolate place to build a colony. The soil was thin and rocky, full of gnarled tree roots. The bay, which they quickly named Cabet Bay, was deep and cold, and high mountains towered over them. Most striking were the woods, a vast impenetrable curtain of greenery made of truly gigantic redwood trees. For people not long removed from temperate France, it seemed a world away. Yet, for those with eyes to see, there was great potential here. For one thing, the looming redwood forests promised a virtually unlimited supply of wood and the deep water was the only such harbor between San Francisco and American-held Oregon. The water teemed with both fish and whales, while the mountains suggested mineral finds for those brave enough to reach them.

The rather imposing shores of Cabet Bay, complete with this grass covered sandbar.

Still, for those first Frenchmen, it seemed an empty, alien land.

Of course, it was not actually empty and before long the Icaraians met the first Wiyot. Out of both personal feelings and blunt necessity Cabet was friendly with the Wiyots, explaining his purpose was to set up a small community near the beach. The Wiyots, puzzled by all of this, simply watched and waited while Cabet and his fellows set about laboriously building a home. They named it L'Esperance, Hope, after an early Cabet publication. Despite quickly building housing, storage and workshops out of the abundant wood, the settlement did not live up to its name.

For one brutal year Cabet stuck to his original plan for creating a communal farming settlement, one of pure self-sufficiency and simplicity. That ideal, of a socialistic utopia of collective farmers nearly spelled the doom of the entire enterprise. Not knowing the local landscape, the Icarians suffered greatly in that first year, struggling to clear the soil and most crops failing anyway. A full third of the would-be settlers abandoned the colony, returning back to San Francisco on one of the irregular visiting French ships. Only the generous spirit of the Wiyots (and the French desperation to trade their few manufactured goods for food) saved L'Esperance from total disaster.

A painting of the leader of the Wiyot's, nicknamed Jean Martin DuBois by the French

The next spring even the stubborn Cabet had to admit that farming, while not impossible in some of the flatter river bottoms, was clearly not how his Icarians would survive in this new environment. In what seems a painfully obvious move they turned to conspicuous wealth all around them. The trees. Timber, sold to San Francisco, was Cabet’s new watchword. Selling timber could provide all the money that his settlement needed to thrive, and not to mention supplying wood for all of their own needs. Cabet’s plans for L'Esperance involved schools and libraries, elaborate town centers and theaters. Perhaps that could all be paid for by lumber instead of produce.

Of course none of the Icaraians were experienced lumberjacks or woodcutters, but they did have the advantage of coming from a nation with a deep and rich history of forest husbandry. Even as Cabet and his utopians struggled and starved in northern Californie, Napoleon III was creating the first nature preserves in the forest of Fontainebleau, protecting them from the hungry axes of the foresters. So with this tradition in mind, Cabet drew up a complex map of forest cuttings and harvesting. Never one to shy away from elaborate plans, Cabet soon had schedules of vast dimensions in both space and time, regulating the careful removal of trees for the next century. With his blueprint in hand, the Frenchmen went forth and began to cut down the forest in earnest.

This sudden change in directions was not lost on the Wiyot people, who missed very little the Eurpoeans did. Their leader, a man the Icarians nicknamed Jean Martin DuBois (of the woods), quickly arrived and inquired about the sudden burst of logging. When Cabet revealed his grand plans, the two soon fell into sharp disagreement. Jean Martin was quite aware that large scale logging would disrupt the local landscape, and adversely affect his people. Still, the French leader did manage to mollify the locals by saying the cutting would be small-scale and, in a rare gesture from a white settler, promised to recompense Wiyot for the loss of their local resources. Assuaged by this arrangement, Jean Martin acquiesced and even offered to help the French, if they were willing to pay.

With this agreement, the French turned to the herculean task of actually logging the redwood forest. These massive trees, many of which rose over two hundred feet into the air, sometimes had bases fifteen to twenty feet in diameter. Worse, since the water-logged wood near the stump would not float (the only possible way of moving the enormous logs once felled), the actual cutting had to take place some twenty feet off the forest floor. High platforms had to be cut and wedged into place, to even begin the work of felling. The Icarians had to wield long axes to cut deep into the redwood’s heart, creating a vast undercut notch, many feet deep. This notch was cut, backcut and finally wedged until the huge tree toppled The first loggers who managed to bring a forest giant down found, much to their dismay, that the brittle redwood would often smash into splinters when it hit the ground, spoiling days or weeks of work. The French learned to create ‘beds’ for the trees to fall into, vast trenches lined with branches and leaves. Then, once safely on the ground, the trunk had to be laboriously rolled (often by brute force of dozens of workers) into a nearby river, to be floated down to the crude sawmill near the shore.

A redwood, shortly before felling.

Still, despite the dangers and difficulties, in the year 1852, the Icarians cut down and processed hundreds of massive trees, sent off to a wood hungry San Francisco. With that income L'Esperance could shift from mere survival to actually thriving, and for the first time, Cabet’s unique social vision started to actually take shape. The Icarians lifestyle was to be dominated by communal activities. They lived together, ate together, and worked together. All apartments had the same furniture, the same clothes, and the same dimensions. Children were raised and educated in communal creches, instead of by their parents. A school was built, as well as a small library and a ramshackle ‘concert hall’ where weekend social events were held. One unusual feature of the small hamlet was what was missing. L'Esperance had no church or formal place of worship. Religion played an unusual role in Icarian thought, difficult for outsiders to understand. They believed in a high power who followed the Ten Principles laid out on Cabet’s writings. While strange, the little settlement prospered enough that a few converts from San Francisco wandered in, drawn by stories filtering south along the lumber trade. Gaining new converts was a novel, but gratifying experience for the Icarians, who finally thought utopia was in sight.

The unusual experiment might have gone one in such a vein indefinitely except for new arrivals to the region in 1853.The Americans had finally arrived.

Drawn toward the northern forests by San Francisco’s endless desire for lumber, they had arrived, axes in hand, to strike it rich among the redwoods. Unlike the cautious Icarcians, the new arrivals had no long term plans or other priorities. Their goal was was cutting down trees and they quickly got down to business. Rude logging camps sprung up all throughout Cabet Bay, virtually ignoring Icarian land grants and Wiyot complaints. The utopians and natives alike quickly found themselves helplessly watching a new found industry explode around them.

And explode it did. In 1852 the Icarians, through great labor, had provided roughly 800,000 board feet of lumber for export. In 1854, after two years of busy expansion the Americans had cut down nearly five millions, with a great deal of growth yet to come. Sawmills ran day and night, using huge sawblades over fifty inches in diameter. Heaps of sawdust piled around the camps, clogging rivers and creating impromptu dams across streams. When the easiest trees were felled, the logger headed further inland, importing teams of oxen to drag the massive logs to the waterside for transport. The redwood empire, the increasingly common name for the area, was clearly under construction.

A team of American oxen pulling a massive log. Note the clear cut forest behind.

It was nothing short apocalypse for the Wiyot. Unlike the Icarians, who had at least taken the Native Americans into account before embarking on new projects, the Americans ignored them viewed them as little more than nuisances to be cleared off the land as fast as possible. It did not take long for violence to break out all over the region, with both sides resorting to raids and ambushes. The loggers, better armed and more numerous, often had the best of the Wylot in these encounters. Untroubled by moral niceties, the whites became quite adept at attacking Wylot villages during festivals or events that kept the men away, leaving the elderly and children as easier targets. The fate of those who survived such attacks was bleak as many were forced into slavery, often acting as forced domestic service for the nearly entirely male population. In a few short years the Wylot world was shattered, and their population in steep decline.

Outraged but impotent to all of this, Étienne Cabet reacted poorly to the turn of events. Unable to confront these new arrivals directly, he did little but send increasingly querulous notes to a distant Mohrenhout, complaining about how the Americans were violating his legal rights. The Governor essentially ignored the complaints however, seeing no meaningful issue. San Francisco needed a gargantuan quantity of lumber and having it from Californie itself was the only way to sustain the explosive Gold Rush induced growth. Morhrehout did not care much if they upset a religious fanatic or destroyed some distant landscape. His only minor concern was if these rough and tumble loggers united with their fellow Americans in Oregon, but the lumbermen exhibited no political aims. Unlike the restless Argonauts, these Americans seemed quite content to make it rich.

Ignored, Cabet withdrew and became increasingly tyrannical over what he could control, L'Esperance. The philosopher began to promulgated ever stricter rules of morality for the settlement. Tobacco and alcohol was banned for all, a curfew enacted and leisure time increasingly surveilled. Cabet even went so far as to forbid idle talk in the workshops during the, increasingly mandatory, working hours. To protect these unpopular regulations, Cabet strove to increase his own power, and extended his term of office indefinitely via changes in the town charter. These moves alienated many in the community, dividing the socialist village against itself. The dispute probably would have ruptured the entire project if Cabet had not suddenly died of a heart attack in 1855.

A modern model of Cabet's dream, a perfect utopia.

Freed of his dominating leadership, the Icarians began to more accurately assess their situation. The arrival of the Americans, while a total disaster for the increasingly fragmented Wylot, were only a mixed blessing for the French. While the Americans had, by sheer dint of numbers, wrestled away most of the lumber trade, the utopians still had considerable assets to draw on. Despite American violations they still had expansive land grants, consisting of the finest timber and most of the water courses. They had friendly relations with the Wylot, which provided labor, resources and information. Lastly, as generally middle class artisans they had labor skills the lumbermen lacked.

With a flexibility that would have shocked Cabet, had he still be alive, the Icarcians once again changed roles. Instead of lumbering directly, they went after the considerable secondary market opened by the inrush of Americans. The Icarians built the blacksmiths and repair shops the loggers needed, the small farms to feed them, the little factories to make nails and machine belts. Icarians sharpened the sawmill blades and built the wagon wheels for the ox teams. The Frenchmen opened a grocery to serve the hungry logging men. Most importantly, the Icarians began their first tentative forays into boat-building, which would have ramifications for generations to come. The only industry the Icarians did not seize was the entertainment district that blossomed along the waterfront, among the warehouses and quays. Nicknamed the Spanish Quarter, it earned fame throughout Californie as the roughest red-light district in the colony.

The dissolute and diverse Spanish Quarter.

In 1857, thriving as middle-men, the Icarians (now led by an executive committee) finally tried to take action against the loggers. Sending a note to San Francisco, they avoided the whining tone Cabet had used, and did not mention their own rights at all. Instead they raised two other points about the lack of an official French presence in Cabet Bay. First was the immorality on display in the Spanish Quarter, a ‘veritable temple to Mammon’ as their letter put it. Did the French leadership really want such a black stain on their colony’s good name? Secondly they hinted that illegal, unregulated trade was happening there, with lumber being diverted away from Californie and to the growing American cities on the Oregon and Washington coasts.

The response to this carefully written appeal was less than the utopians had hoped. A small detachment of two dozen French marines arrived, as well as a few would-be sheriff deputies. Barely enough to survey the transgressions, let alone meaningfully counter them. Unbeknownst to everyone however, one of the men in the new arrivals would change the fate of the redwood empire forever. An artistic leaning young soldier named Oscar-Claude Monet would, some day, become synonymous with the northern woods for reasons quite beyond anyone’s guess.

A picture of Claude Monet in 1858, as yet, no one of importance.

Beautiful vistas, interesting people, whores...yeah, the Impressionists are gonna love it here.

Great chapter , i dont really care if the socialist utopia failed , those type of things never work , and there is always some creepy elements present in those comunities , they are much better as middleman in smal business, whats the population ? it mustbe growing very fast , also is there a very strong frensh imigration to the colony ?

To be fair, the Icarians still hold several unusual philosophical and religious views, so the experiment isn't dead perse. Population of the whole region? I'm not sure, I'd have to check some numbers. There is high immigration from all over the world to Californie, but yes, many from France. This will be touched on later. ironically, as the American lumber camps turn to proper corporations, they will hire French lumberjacks the most. Like in OTL, they turned out to be the best at logging.Great chapter , i dont really care if the socialist utopia failed , those type of things never work , and there is always some creepy elements present in those comunities , they are much better as middleman in smal business, whats the population ? it mustbe growing very fast , also is there a very strong frensh imigration to the colony ?

twovultures

Donor

As we all know from the story of Jean-Paul Bougnon.ironically, as the American lumber camps turn to proper corporations, they will hire French lumberjacks the most. Like in OTL, they turned out to be the best at logging.

Why doesn't he see an issue?The Governor essentially ignored the complaints however, seeing no meaningful issue.

It would seem advisable to send at least a token force to assert French control of the area as soon as Americans start arriving.

"Pfft, let them fight. Wake me up when there's an actual shooting war like the one we just had."Why doesn't he see an issue?

It would seem advisable to send at least a token force to assert French control of the area as soon as Americans start arriving.

There isn't much to go around. Also, 'no' presence is mostly Cabet carping. Just no real meaningful French presence. This is still early days, after all.Why doesn't he see an issue?

It would seem advisable to send at least a token force to assert French control of the area as soon as Americans start arriving.

Post #19- Southern Californie

Post #19- Southern Californie

Nothing attracts the powerful quite like more power.

Ben Aaronovitch

Compared to the bustling, bumptious north, southern Californie unfolded like a sleepy dream, gently swaying to the rhythms of the past. This was a land that seemed old, quite apart from the raw civilization being hacked out of the earth in other parts of the colony. A people that prided itself on historic and honored tradition. A land of bullfights and fandangos, of the smell of orange blossoms and dusty evenings. The leading elite families of Californios ruled as they had for generations, controlling vast estates and cowherds throughout the area, turning hides and tallow into fortunes. The arrival of the French in 1836, just like Mexican independence before it, had done little to interrupt the delicate social and political dances of the Sepúlvedas, Lugos and Carrillos. Every family had their own small fiefdoms of estates, towns and vaquero cowboys to do their bidding.

There had been some minor changes in the last few decades, of course. Monte Rey, and later San Francisco gathered more in taxes then Mexico City ever had but this was hardly a true hardship. Several of the old Mexican-era land grants had been renegotiated or challenged and a few new landowners emerged but nothing that substantially altered the balance of power. The tiny French garrisons along the coast were generally too small to impact the order of things, and the few French officials who penetrated the corridors of power were usually sucked into the game, not disruptive to it.

Andres Pico, wearing traditional Californio elite clothing

The only real change had been the evolving French policy regarding the Native Americans. Previously the ruling Californios had generally ignored the native peoples of the area, either confining them to the mission plantations to be ‘civilized’ or working to expropriate them from valuable lands. Now however, some tribal lands were to be protected from white settlers, and certain native rights, such as hunting or travel, were to be legally respected. This new status only affected those tribes, such as the Kumeyaay, that the French deemed as valuable allies. Yet even that partial recognition was a meaningful change for the established Californios who were forced to concede to the original inhabitants of the region, where before they did as they liked.

Even the Gold Rush, that seminal event of the Pacific world, seemed to affect southern Californie very little, at least at first. The initial impact was merely a vast upswing in prices for the cattle, now valuable for their meat instead of hides. The herds doubled, trebled and then exploded to ten times their old numbers. Prices soared to astronomical heights, enriching the old Californio elites even more, entrenching the existing power structures. The coastal towns of Los Angeles and San Diego hummed with new activity as the docks filled with fleets of incoming ships, all headed for the northern goldfields. This transient population left little impact aside from boosting demand even higher, but the same could not be said of the Overlanders.

American prospectors resting during the grueling journey through the desolate regions of the southern emigrant trail.

These were the prospectors drawn to Californie and arrived via the Southern Emigrant Trails, varying paths that led from Sante Fe through the desert to Yuma and beyond. While most of these trekkers quickly passed through the region toward the north, more than a few remained in the south. This steady influx of English speaking Americans changed the character of the region permanently, creating a sharp divide between the landed gentry and those below. The Californios snubbed the newcomers, viewing American attempts to become mayors or town leaders with either contempt or alarm. Even the simple purchase of land became a political and cultural battlefield, as the Californio establishment did their best to sabotage such efforts, by any means necessary. Feeling legally trapped, the Americans often struck back with violence, which led to clashes with the Californio vaqueros, sent to enforce landowner demands. This unrest boiled over to the local native american tribes as well, resulting in disturbances like the 1853 Yuma War, only ended by the surprise arrival of Bazaine and the French Foreign Legion.

The presence of the Legion shifted the balance of power and for the first time, the French had, at least in theory, the ability to enforce their wishes. Morhrenhout soon found himself inundated with letters from every faction, seeking to have French power weigh in on an issue. Everything from complaints about land grant arbitration, voter franchise laws to Native Mmerican grazing rights arrived on the Governor's desk, adding to an ever increasing pile. Even with the best will in the world, it was impossible for San Francisco to even answer, let alone solve, all of the problems sent north. Into this geographically induced gap of authority slipped François Achille Bazaine.

While his legal authority as Inspector General of the Legion in Californie was murky at best, he was clearly the French man on the spot and quickly became the most sought after man in the entire region. While Bazaine ran the Legion itself like an austere monk (he demanded the legionaries wash their own clothes and even tried to have them maintain their own gardens), personally he had no objection to the finer things in life. Soon the French commander was roaming southern Californie like a feudal lord, being entertained at every stop by Californios and Americans alike. The Frenchman even included the Native Americans in his rota, meeting regularly with Kumyeeay leaders, who he viewed as a valuable source of loyal manpower. Bazaine even went so far as to include several other tribes into the pro-French alliance structure forming in the region, namely the Cahuilla and Acjachemen peoples.

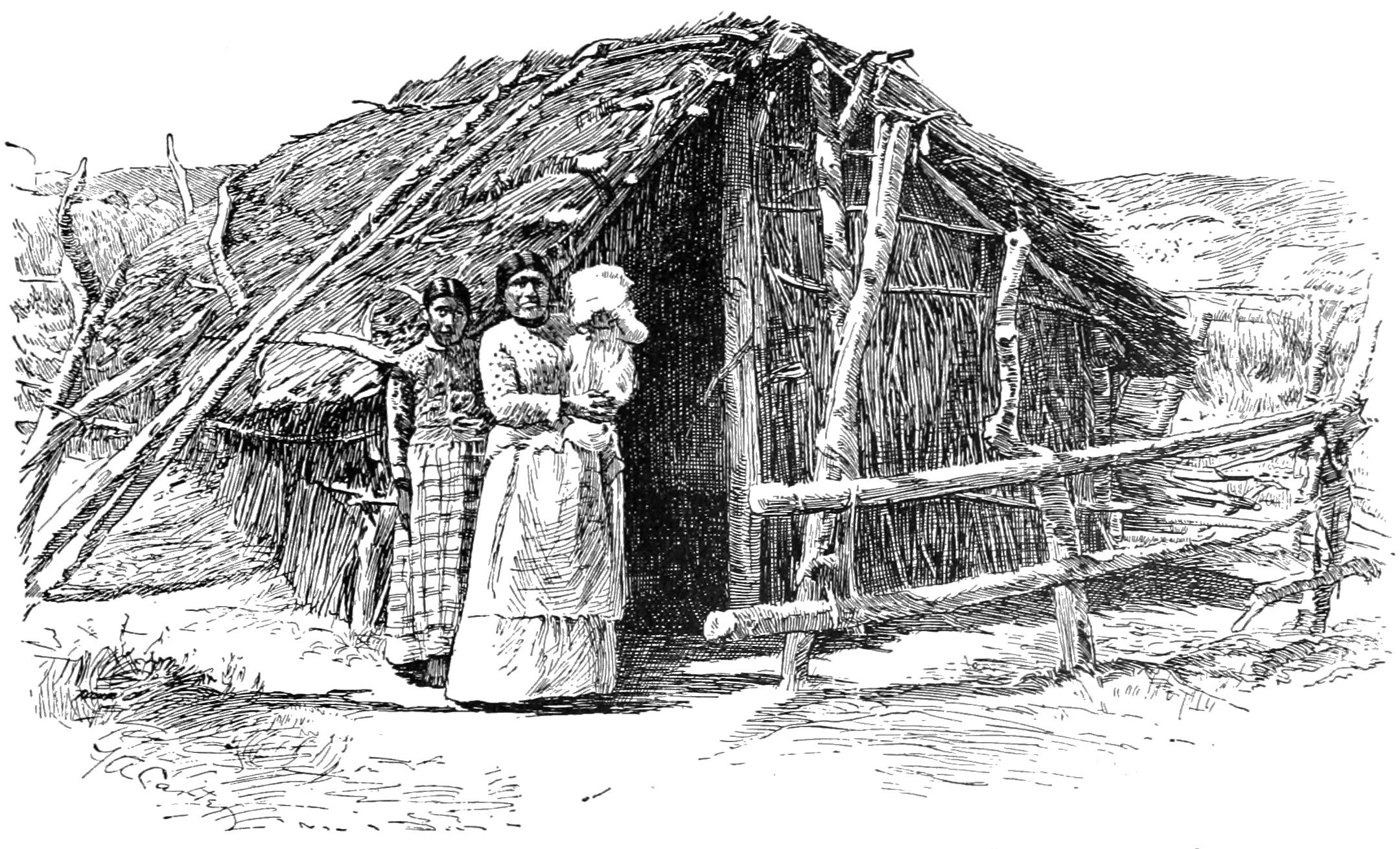

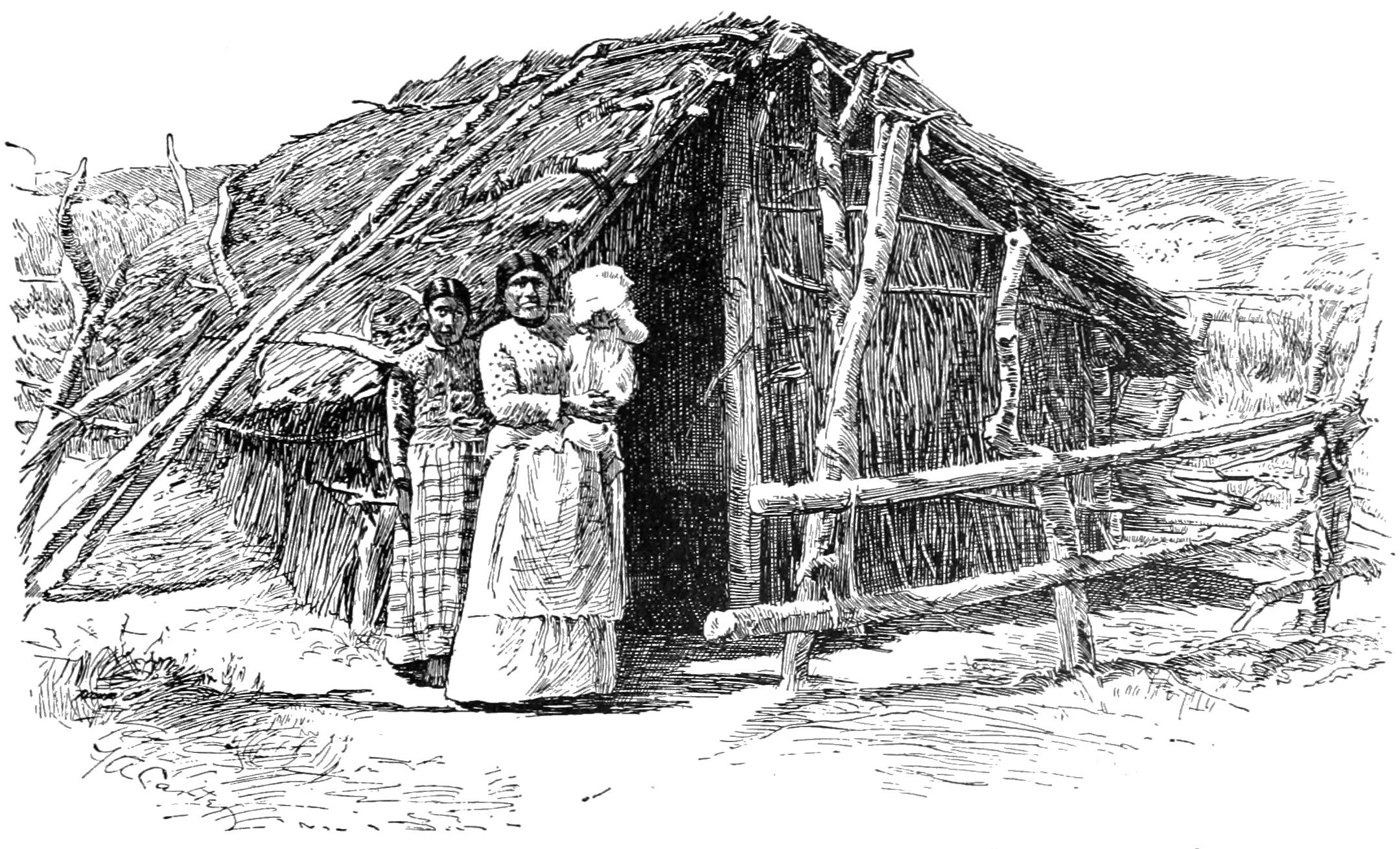

A simple Cahullia hut, a people pushed into French alliance due to desperation

Still, Bazaine primarily had to deal with the increasingly hostile American and Californio relations. Favoring neither side totally, the Legionnaire generally obliged whoever could better support the Legion in the region. Promises of money, supplies, and especially recruits swayed Bazaine far more than legal argumentation. So it was that the Legion commander traveled around his new domain as kingmaker, hearing out disputes that the thinly spaced French judges had been unable to solve. Sometimes Bazaine only promised to send letters of recommendations north, to vouch for this choice or that action. Oftentimes however, the commander decided the dispute fell within his murky jurisdiction and took an immediate hand in the problem. His pronouncements were rarely questioned, no one wanted to get on the wrong side of the Legion commander. Bazaine may not come if a settlement was under an attack or if a riot got out of control.

When word of these decisions reached San Francisco Morhrehout was distressed but could do little about it. While he, as Governor of Californie, certainly outranked Bazaine, the distinction was unclear enough to preclude simply ordering the commander to desist. Such a command would have to go through Paris and become part of a complicated and intricate bureaucratic mess happening on the other side of the planet. Morhrehout consoled himself that at least Bazaine was keeping the peace and consolidating French power in the southern reaches of the colony. It was better than nothing.

The Legion’s troops were not kept idle during this period, far from it. While their commander wined and dined with the local elite, the humble soldiers were busy out in the field. Quite apart from the considerable task of turning Fort Yuma into a proper headquarters worthy of the Legion, they graded roads, built outposts and organized depots across the region. The men also had need of their weapons as well. In 1854, Bazaine began a systematic and organized campaign against the troublesome bandidos, who made tempting targets for repression. The bandits had no allies, no real base of support. No one would be upset at seeing a bandido hang.

So for the next three years the Legion worked to suppress the rogue vaqueros, outlaws and robbers that lurked all throughout the territory. It was tedious work, often involving long treks to isolated corners of the landscape and laboriously (sometimes literally) digging out criminals from hideouts. Most were little more than local bullies of course, small time criminals who ambushed a wagon or two for a season. The Legion captured dozens of these, arresting and sending them off to the civil authorities in Los Angeles or San Diego to deal with, which generally meant execution but sometimes merely hard labor or transportation. While welcomed by the local population, these were not Bazaine’s main quarries. The Frenchman was not after part-time criminals, but the legendary bandidos who embroidered every gold-miner’s tale, every traveler’s yarn.

Finally in 1856 one was brought to heel, the semi-mythical Anastacio Garcia whose fame was only surpassed by Joaquin Murrieta (who operated near the northern goldfields, well out of the Legion’s current reach). Garcia was renowned not only by his daring criminal deeds but also the political bent of his activities, generally only striking at French or American targets. This put him at the top of Bazaine’s list but despite several close shaves it took years for the legionaries to finally catch up with the bandit, capturing him in a dramatic battle at his hideout, an imposing natural fortification later known as Le refuge du voleur in the remote interior. Captured alive, Garcia’s arrival in Los Angeles caused one of the first media sensations in southern Californie history, with several of the San Francisco newspapers rushing to capture the man’s last words. A crowd of thousands, including Bazaine himself, watched the famed outlaw hang on October 21, 1856.

Le refuge du voleur in the northern Mojave

Despite official French policy, Bazaine also frequently got tangled up in Native American conflicts as well. The price of allying with some tribes was, of course, defending them against their own neighbors. Several times the French commander led his men in person (and twice under fire) against recalcitrant native peoples. The most wide ranging conflict was the Yokuts War, which led Legionnaire troops as far north as the shores of Lake Tulare. The war, which had started with the French defending the friendly Chumash from Yokuts raiders soon developed into a brutal campaign of destruction and extermination. The virtual genocide was one of the darker stains on the French Californie project, but not the last.

Nothing attracts the powerful quite like more power.

Ben Aaronovitch

Compared to the bustling, bumptious north, southern Californie unfolded like a sleepy dream, gently swaying to the rhythms of the past. This was a land that seemed old, quite apart from the raw civilization being hacked out of the earth in other parts of the colony. A people that prided itself on historic and honored tradition. A land of bullfights and fandangos, of the smell of orange blossoms and dusty evenings. The leading elite families of Californios ruled as they had for generations, controlling vast estates and cowherds throughout the area, turning hides and tallow into fortunes. The arrival of the French in 1836, just like Mexican independence before it, had done little to interrupt the delicate social and political dances of the Sepúlvedas, Lugos and Carrillos. Every family had their own small fiefdoms of estates, towns and vaquero cowboys to do their bidding.

There had been some minor changes in the last few decades, of course. Monte Rey, and later San Francisco gathered more in taxes then Mexico City ever had but this was hardly a true hardship. Several of the old Mexican-era land grants had been renegotiated or challenged and a few new landowners emerged but nothing that substantially altered the balance of power. The tiny French garrisons along the coast were generally too small to impact the order of things, and the few French officials who penetrated the corridors of power were usually sucked into the game, not disruptive to it.

Andres Pico, wearing traditional Californio elite clothing

The only real change had been the evolving French policy regarding the Native Americans. Previously the ruling Californios had generally ignored the native peoples of the area, either confining them to the mission plantations to be ‘civilized’ or working to expropriate them from valuable lands. Now however, some tribal lands were to be protected from white settlers, and certain native rights, such as hunting or travel, were to be legally respected. This new status only affected those tribes, such as the Kumeyaay, that the French deemed as valuable allies. Yet even that partial recognition was a meaningful change for the established Californios who were forced to concede to the original inhabitants of the region, where before they did as they liked.

Even the Gold Rush, that seminal event of the Pacific world, seemed to affect southern Californie very little, at least at first. The initial impact was merely a vast upswing in prices for the cattle, now valuable for their meat instead of hides. The herds doubled, trebled and then exploded to ten times their old numbers. Prices soared to astronomical heights, enriching the old Californio elites even more, entrenching the existing power structures. The coastal towns of Los Angeles and San Diego hummed with new activity as the docks filled with fleets of incoming ships, all headed for the northern goldfields. This transient population left little impact aside from boosting demand even higher, but the same could not be said of the Overlanders.

American prospectors resting during the grueling journey through the desolate regions of the southern emigrant trail.

These were the prospectors drawn to Californie and arrived via the Southern Emigrant Trails, varying paths that led from Sante Fe through the desert to Yuma and beyond. While most of these trekkers quickly passed through the region toward the north, more than a few remained in the south. This steady influx of English speaking Americans changed the character of the region permanently, creating a sharp divide between the landed gentry and those below. The Californios snubbed the newcomers, viewing American attempts to become mayors or town leaders with either contempt or alarm. Even the simple purchase of land became a political and cultural battlefield, as the Californio establishment did their best to sabotage such efforts, by any means necessary. Feeling legally trapped, the Americans often struck back with violence, which led to clashes with the Californio vaqueros, sent to enforce landowner demands. This unrest boiled over to the local native american tribes as well, resulting in disturbances like the 1853 Yuma War, only ended by the surprise arrival of Bazaine and the French Foreign Legion.

The presence of the Legion shifted the balance of power and for the first time, the French had, at least in theory, the ability to enforce their wishes. Morhrenhout soon found himself inundated with letters from every faction, seeking to have French power weigh in on an issue. Everything from complaints about land grant arbitration, voter franchise laws to Native Mmerican grazing rights arrived on the Governor's desk, adding to an ever increasing pile. Even with the best will in the world, it was impossible for San Francisco to even answer, let alone solve, all of the problems sent north. Into this geographically induced gap of authority slipped François Achille Bazaine.

While his legal authority as Inspector General of the Legion in Californie was murky at best, he was clearly the French man on the spot and quickly became the most sought after man in the entire region. While Bazaine ran the Legion itself like an austere monk (he demanded the legionaries wash their own clothes and even tried to have them maintain their own gardens), personally he had no objection to the finer things in life. Soon the French commander was roaming southern Californie like a feudal lord, being entertained at every stop by Californios and Americans alike. The Frenchman even included the Native Americans in his rota, meeting regularly with Kumyeeay leaders, who he viewed as a valuable source of loyal manpower. Bazaine even went so far as to include several other tribes into the pro-French alliance structure forming in the region, namely the Cahuilla and Acjachemen peoples.

A simple Cahullia hut, a people pushed into French alliance due to desperation

Still, Bazaine primarily had to deal with the increasingly hostile American and Californio relations. Favoring neither side totally, the Legionnaire generally obliged whoever could better support the Legion in the region. Promises of money, supplies, and especially recruits swayed Bazaine far more than legal argumentation. So it was that the Legion commander traveled around his new domain as kingmaker, hearing out disputes that the thinly spaced French judges had been unable to solve. Sometimes Bazaine only promised to send letters of recommendations north, to vouch for this choice or that action. Oftentimes however, the commander decided the dispute fell within his murky jurisdiction and took an immediate hand in the problem. His pronouncements were rarely questioned, no one wanted to get on the wrong side of the Legion commander. Bazaine may not come if a settlement was under an attack or if a riot got out of control.

When word of these decisions reached San Francisco Morhrehout was distressed but could do little about it. While he, as Governor of Californie, certainly outranked Bazaine, the distinction was unclear enough to preclude simply ordering the commander to desist. Such a command would have to go through Paris and become part of a complicated and intricate bureaucratic mess happening on the other side of the planet. Morhrehout consoled himself that at least Bazaine was keeping the peace and consolidating French power in the southern reaches of the colony. It was better than nothing.

The Legion’s troops were not kept idle during this period, far from it. While their commander wined and dined with the local elite, the humble soldiers were busy out in the field. Quite apart from the considerable task of turning Fort Yuma into a proper headquarters worthy of the Legion, they graded roads, built outposts and organized depots across the region. The men also had need of their weapons as well. In 1854, Bazaine began a systematic and organized campaign against the troublesome bandidos, who made tempting targets for repression. The bandits had no allies, no real base of support. No one would be upset at seeing a bandido hang.

So for the next three years the Legion worked to suppress the rogue vaqueros, outlaws and robbers that lurked all throughout the territory. It was tedious work, often involving long treks to isolated corners of the landscape and laboriously (sometimes literally) digging out criminals from hideouts. Most were little more than local bullies of course, small time criminals who ambushed a wagon or two for a season. The Legion captured dozens of these, arresting and sending them off to the civil authorities in Los Angeles or San Diego to deal with, which generally meant execution but sometimes merely hard labor or transportation. While welcomed by the local population, these were not Bazaine’s main quarries. The Frenchman was not after part-time criminals, but the legendary bandidos who embroidered every gold-miner’s tale, every traveler’s yarn.

Finally in 1856 one was brought to heel, the semi-mythical Anastacio Garcia whose fame was only surpassed by Joaquin Murrieta (who operated near the northern goldfields, well out of the Legion’s current reach). Garcia was renowned not only by his daring criminal deeds but also the political bent of his activities, generally only striking at French or American targets. This put him at the top of Bazaine’s list but despite several close shaves it took years for the legionaries to finally catch up with the bandit, capturing him in a dramatic battle at his hideout, an imposing natural fortification later known as Le refuge du voleur in the remote interior. Captured alive, Garcia’s arrival in Los Angeles caused one of the first media sensations in southern Californie history, with several of the San Francisco newspapers rushing to capture the man’s last words. A crowd of thousands, including Bazaine himself, watched the famed outlaw hang on October 21, 1856.

Le refuge du voleur in the northern Mojave

Despite official French policy, Bazaine also frequently got tangled up in Native American conflicts as well. The price of allying with some tribes was, of course, defending them against their own neighbors. Several times the French commander led his men in person (and twice under fire) against recalcitrant native peoples. The most wide ranging conflict was the Yokuts War, which led Legionnaire troops as far north as the shores of Lake Tulare. The war, which had started with the French defending the friendly Chumash from Yokuts raiders soon developed into a brutal campaign of destruction and extermination. The virtual genocide was one of the darker stains on the French Californie project, but not the last.

Last edited:

Changed, thank you.very good chapter and Robber's Roost shouldn't it be called " Le refuge du voleur " since there is less Anglophone influence?

Share: