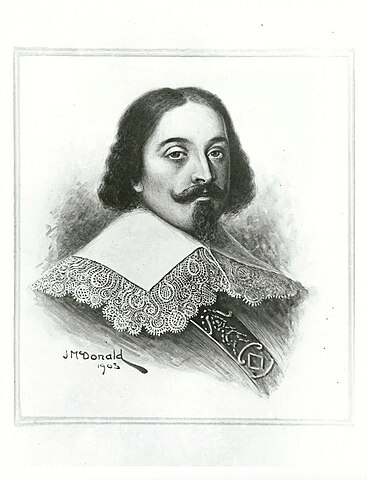

Shi Kefa, up-and-coming bureaucrat in the Ministry of Works

In Rome, Pope Urban VIII dies. He leaves behind him a legacy that touches most of Europe and occasionally lands farther afield -- even China. An eloquent man, the author of some decent hymns, the promulgator of papal bulls condemning such sins as slavery and the use of tobacco. He had proven himself a friend of the Jesuits (who are grateful to him), confirming the legitimacy of their missions in the New World and in China. He reigned as both vicar of Christ and as a secular prince, seizing the Duchy of Castro by force of arms. He canonized several saints and created more than seventy cardinals, including at least four of his own blood relatives.

And now he’s dead. He is succeeded by one of the cardinals he’d created, Giovanni Battista Pamphili, who takes the name Innocent X.[1]

The new pope inherits a papacy greatly depleted of funds -- wars are expensive -- which he tries to recoup in part by seizing properties owned by the late pope’s relatives. (He’s a little upset with them. You see, apart from the usual politicking, some years ago the late pope’s brother had commissioned a painting where the Archangel Michael is trampling a Satan who greatly resembles Cardinal Pamphili, an act viewed as gravely insulting and for which Innocent X has never quite forgiven them.[2])

Pope Innocent X is also a little bemused by one action recorded in the papal records -- among the many cardinals appointed by his predecessor, several had been created in pectore, which is to say secretly, in the custom of the church -- and while Urban VIII had eventually published most of their names, he died without revealing the name of the last one (although there are some reports that he attempted to do so on his deathbed). This isn’t the first time that such a thing has occurred, but it’s still odd.[3] The new pope shrugs and gets on with his work.

Now let’s swing back to our usual stomping-grounds. Injo of Joseon, who had reigned since a 1623 palace coup put him in power, dies after a sudden illness. He is succeeded by his eldest son, the Crown Prince Sohyeon.

Some whisper about skullduggery afoot. The late king had been in apparent good health right before he died, and naturally there are rumors of poison. Adding to the mystery, his heir Sohyeon had evidently been gravely ill but had recovered. Historians debate the exact sequence of events which had taken place. The consensus view, in line with that expressed by the Ming chronicler Zhong Hecao, is that both individuals fell ill in close succession due to a contagious disease or inadvertent contamination. This “official” record of events was likely adapted verbatim from the more comprehensive Annals of the Joseon Dynasty. However, revisionist historians have posited that either both men were poisoned by an outside force, or that Injo (for uncertain reasons) had attempted filicide, and was subsequently assassinated by some agent loyal to Sohyeon. These interpretations have inspired numerous fictional works but, truthfully, the full story may never be told. Maybe there was some kind of conspiracy in the Joseon court, but its participants, if any, have yet to be identified.

So who is the newest king of Joseon? He is often compared to his father, who was regarded as a reliable pro-Ming figure, although obviously the nobles of Joseon are positively inclined towards their large, powerful neighbor in general. That said, some historians criticize Injo as a vacillating, ineffective personality who “got lucky” by happening to be king at a time when first the Ming and later the Northern Yuan flexed their might in destroying his most immediate geopolitical foe, the Later Jin.[4] In contrast, his son is regarded as more thoughtful, open-minded, and decisive -- at least, that’s what his supporters hope.

The former Crown Prince assumes the temple name of Hyojong upon his accession. His foreign wife, Erdani, gives birth to the couple’s first child, Yi Seok-rin, a healthy boy who is granted the title of Crown Prince Gyeongwan.[5]

The Joseon court is very much continuing their usual polite relations with their nominal suzerain (the Empire of the Great Ming) but are also interested in cooperation with the Northern Yuan -- the king loves his wife -- so things might get interesting.

Shifting our attention to Dongshan, the island is rocked by the publication of -- no, it’s not an economics treatise from Di Yimin. It’s a rambling religious text of uncertain authorship but often attributed to Amakusa Shirō a.k.a. Geronimo (sometimes described in European sources as “Geronimo Amakusa”), the charismatic Japanese Christian and figurehead of an abortive rebellion, who has resided on Dongshan since 1638 when he and his followers were evacuated by Admiral Zheng’s fleet.[6]

The document is not a work of great literature by any standard. Sometimes called the Pearl of Great Price (after the Biblical passage which it extensively references), the book recounts a series of surreal (and sometimes erotic) images personally revealed to Geronimo over the course of his life, brought to him by an Angel of the Lord, because he has been blessed with a direct line of communication with the Christian divinity, and he’s been ordered to share his message with everyone in the empire, because the Lord has a special interest in China, obviously. The Pearl is easy enough to read, and while its authorship may be questionable it is swiftly adopted and reprinted by Geronimo’s religiously heterodox followers.

Responses are mixed. These people are a dedicated bunch who are already convinced that their leader works miracles, leading to some curiosity from their neighbors. Actual Christians in China are less curious and more dismissive -- Nicolas Trigault writes some disapproving words back to Rome reporting on the actions of “Balaam over the sea” which is probably a reference to Geronimo and the allegedly licentious ways of his followers. Obviously, there is no such thing as a (Catholic) Chinese Inquisition. Geronimo’s followers might be fined by local magistrates for disturbing the peace, but they won’t be burnt at the stake -- in China, at least. In the Philippines and Macau, the authorities there would probably disapprove. Admiral Zheng in Dongshan doesn’t care much, since Geronimo’s followers are among the foremost of the settlers willing to take up residence in the backcountry, and he needs all the people he can get -- there’s rumblings of war with the Dutch, and also he’s been having some trouble with the indigenous population. But we’ll get to that later.

Oh, yes, and Geronimo’s getting attention outside of his usual circles. The poet Wang Wei mocks him as the “leader of little fishes” which swim about in the sea, since that is where pearls can be found -- it’s an idea which swiftly finds approval among Geronimo’s actual followers, who start calling themselves the Fishermen (for Biblical reasons). Although the Fishermen by and large aren’t actually fishermen, who have more interesting gods. Still, awareness is starting to spread. The small Christian community, both foreigners like the Jesuits and local converts, think that Geronimo is one weird guy. Politically conservative members of the imperial court grumble that things weren’t like this back in the good old days.

Speaking of the imperial court, Dong Kewei, at the Ministry of Works, is reviewing a report drafted by his deputy Shi Kefa.[7] China’s canals are more or less functional, thanks to the Ministry being mostly competent (also because Minister Dong, as the emperor’s unofficial spymaster, wields a lot of soft power that’s technically outside of his legal remit, so his expenditures get approved very quickly). But canals aren’t the only waterways in China. There are rivers, some of which are quite large.

Shi Kefa writes that he had by chance heard of the Ming ancestral tombs which the Hongwu Emperor had built along the banks of the Hongze Lake. These are not technically imperial tombs -- the emperors themselves are interred elsewhere -- but the Hongwu Emperor was really big into lavish building projects to honor his ancestors.[8] The mortuary complex near Hongze Lake contains the remains of the Hongwu Emperor’s grandfather and empty tombs for more distant ancestors. It is perhaps less important than other Ming imperial mausoleums, but it’s still important.

It is also in danger. Shi Kefa warns that the tomb is built perilously close to the shores of the lake. This was done for reasons of feng shui, which is well and good, but the people who built the place didn’t take many precautions to prevent flooding. And Hongze Lake is fed by the river Huai. Now, the Huai River, like most of China’s large, silt-heavy rivers that flow from west to east, is prone to flooding. It’d only take a really bad season, or a silt clog somewhere down the line, before something catastrophic happened. So, since Shi Kefa is looking for a new project (and because he wants to make his name, since his boss is gonna retire someday and he wants to be Minister of Works when that happens), he suggests a project to either redirect the flow of the Huai or, if that is impractical, to construct large dikes or other earthworks to protect the ancestral tombs, just in case. Minister Dong is a little skeptical of his subordinate’s analysis, but he appreciates the effort, and he figures that it’ll create employment for the locals, so he signs off on the second plan to build dikes.[9]

There’s bloodletting elsewhere in the world -- the Portuguese and Spanish are still killing each other -- but for China, in the here and now, these are peaceful days.

Footnotes

[1] All this is OTL thus far. I can’t think of anything that would have changed any of this -- Ming influence has resulted in Lorenzo Ruiz and Francesc de Borja being canonized ahead of schedule but wouldn’t have shifted the balance of power in the College of Cardinals, so the 1644 conclave proceeds as normal. Pope Innocent X is probably best-known as the guy in a truly excellent painting by Diego Velasquez, and then in some more disturbing paintings by Francis Bacon.

[2] This happened IOTL.

[3] Pope Pius IV created a cardinal in pectore at the consistory of 1561 and failed to publish the name before death, the only earlier example of this kind of mishap that I can find. For more information on the practice of in pectore, I recommend Wikipedia. You can speculate as to the identity of Urban VIII’s secret cardinal -- who is not listed as one of Urban VIII’s OTL cardinals -- and why I have mentioned this seemingly minor incident in my timeline.

[4] This is pretty much the OTL consensus on Injo, except he had to submit to the Qing and also IOTL was probably successful in murdering his son. ITTL he has his detractors but Joseon did well under his reign, so he comes off a little better.

[5] The temple name is the same as the one his brother took upon ascending the throne IOTL -- and, for that matter, the name / title that he gives his son is the same as one of his OTL children. What can I say? I’m lazy.

As an aside, many East Asian royal figures of this time period are commonly described by their temple names -- some Chinese dynasties are described this way by convention, although for Ming emperors the custom is to describe them with their era names. So, for example, our guy the Tianqi Emperor is so called because his era was that of a “heavenly opening;” he was given the name Zhu Youjiao at birth and received the temple name Xizong. Don’t worry about it too much. I try to be consistent, at least, with how I refer to people, and if I make a goof then that’s on me.

[6] Remember him? The Shimabara Rebellion may have fizzled out ITTL but its legacy lives on.

[7] For a review of who’s who in the bureaucracy, refer to Dramatis Personae [1638] and the updated list of top officials in 1641.

[8] This was mentioned previously in 1634. The tombs mentioned previously in Fengyang are often called Huangling while the ones mentioned in this update near Hongze Lake are often called Zuling.

[9] Shi Kefa has good instincts. IOTL nobody paid much attention to the tombs, partly because the Ming dynasty was collapsing and the Qing dynasty was still figuring stuff out. Consequently in 1680 when the Yellow River suddenly changed course and started flowing into the Huai, massive amounts of water entered Hongze Lake and completely submerged the Zuling tombs. They were not seen again for approximately three hundred years.