You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Stars and Sickles - An Alternative Cold War

- Thread starter Hrvatskiwi

- Start date

-

- Tags

- cold war

Threadmarks

View all 122 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 98: The Conqueror? - Uganda (Until 1980) (Part 2) Chapter 99: Slaying the Beast - Uganda (Until 1980) (Part 3) Chapter 100 [SPECIAL] - Ad Astra - Aerospace Competition Between the Superpowers (Until 1980) (Part 1) Chapter 101 [SPECIAL] - Magnificent Desolation - Aerospace Competition Between the Superpowers (Until 1980) (Part 2) Chapter 102: Jadi Pandu Ibuku - Nusantara (Until 1980) Chapter 103: Furtive Seas - South Maluku and West Papua (Until 1980) Chapter 104: Kings and Kingmakers - Post-Independence North Kalimantan (Until 1980) Chapter 105: Maka-Diyos, Maka-Tao, Makakalikasan, at Makabansa - The Philippines (Until 1980)Kindly give an update on the Indian subcontinent.

I was actually thinking about that the other day. I will include one in the next few updates, but I really need to do some more research to give it the love it deserves. Any ideas for the update or sources that're useful?

Chapter 18a: The Pipeline - Kenyan Decolonisation (1950s)

A New World (1950s): The Pipeline (Kenya Pt.1)

Challenges to British colonial rule in Kenya developed in the immediate post-war period, coming to a head in the 1950s with the so-called Mau Mau Rebellion. To understand this rebellion, as with most major civil conflicts, we must examine the structure of colonial society in British Kenya and the manner in which it marginalised the native peoples.

The native population of the colony was divided between a variety of ethnic groups of both Bantu and Nilotic origin. The main Bantu groups were the Gĩkũyũ (Kikuyu), Amîîrú (Meru), AbaGusii (Kisii), Embu, Wakamba (Akamba), Abaluyia (Luhya), Waswahili (Swahili) and Mijikenda peoples. Major Nilotic groups included the Joluo (Luo), Maasai (Masai), ŋiTurkana (Turkana), Loikop (Samburu) and Kalenjin. The largest of these were the Gĩkũyũ and the Joluo.

The largest ethnic group in British Kenya (and the primary contributors to the Mau Mau forces) were the Gĩkũyũ, whose homeland lay in the Western foothills of Mount Kenya, known to the Gĩkũyũ as Kĩrĩ Nyaga (where God lives). The 1939 White Highlands Order expelled natives (largely Gĩkũyũ) from hill farms reserved for European settlement and known as "the White Highlands". Although native dispossession and European (largely British) settlement in the Highlands had been ongoing for several decades, large native populations remained in the role of farmhands, living on their ancestral land with the permission of their employers. As mechanisation reached colonial Kenya from Britain in the 1930s, however, the demand for cheap manual labour lessened dramatically. Remaining native squatters were subjected to oppressive labour contracts and the colonial administration also limited the number of livestock individual Gĩkũyũ could own. The limitations on native property instituted by the colonial administration created significant pressure on a society which highly valued land ownership and used cattle as currency.

These pressures established a social dimension to what is often considered in the West to have been an anti-colonial struggle between monolithic native and British blocs. The limitation of grazing to defined native reserves placed stress on finite (and often comparatively poor, compared to those in the White Highlands) resources. Those most severely affected by the new legislation were the landless men ("ahoi") and guest residents ("jodak"). Founder lineages within Gĩkũyũ society increasingly sought total control over property they claimed to be theirs. Aware of the pressures on Gĩkũyũ society, the colonial administration tried to improve productivity of native reservations through the introduction of bench-terracing to increase agricultural yields. Whilst this policy seemed applaudable, this particular policy was viewed with suspicion by the natives. It did increase demand for manual labour again, but natives were often coerced into working and purposely put up resistance to the works. The Joluo people in particular were staunchly opposed, fearing (like many other natives) that the British were merely trying to garner support and intended to confiscate the hills once they were made productive.

Adding to the rapidly changing social environment within native society were the "keya", African soldiers returning from service in WWII. These keya brought back with them valuable capital which they invested in small businesses, such as shops, tea-rooms, water-mills, lorries and buses. The increasing importance of keya in Gĩkũyũ society brought them into conflict with traditional social forces, namely the chiefly and "karani" (cleric) class. This tension has been characterised by Marxist analysts as a contest between "progressive" urban keya and "reactionary" rural chiefs/karani. The most severe tension, however, was between the natives and the (South) Asian traders which were the primary competitors with the emerging native entrepeneurs who wanted to establish an independent native middle-class, as opposed to the Asian middle class that relied on colonial patronage.

Given restrictions on African political activity, there were only two avenues available to political representation of the African entrepeneurs: the Kenya African Union (KAU) or collaboration with the colonial government. Those that joined the KAU tended towards moderate nationalism, siding with the like of Jomo Kenyatta. They therefore played very little active role in the Mau Mau Rebellion itself, although they would be profoundly impacted by the social restructuring afterwards. Nevertheless, Kenyans of all social standings experienced similar discrimination in the segregated colonial society. In the capital, Nairobi, and other major cities such as Malindi and Lamu, European settlers lived separately from the African population. A formal colour bar excluded natives from access to sanitary urban housing, wages, adequate schooling and infrastructural support. Urban opportunities were few, with very limited licenses for African traders and the largest employers offering little more than manual dock labour to Africans.

Sir Philip Euen Mitchell was the Governor of British Kenya between 1944 and the summer of 1952, when he retired. Mitchell had taken a very light stance on the Mau Mau forces which had started to attack African collaborators. These attacks were dismissed by Mitchell as isolated incidents, not as part of a wider politico-military campaign. Mitchell was replaced by Henry Potter, who for a short period was Acting Governor. The Colonial Office received regular reports from Potter about escalating Mau Mau violence, but it wasn't until late 1953 that the Colonial Office recognised the seriousness of the rebellion.

On 30 September 1952, Sir Evelyn Baring, son of the first British governor of Egypt, replaced Potter permanently. Baring was forced to proverbially "hit-the-ground-running" due to the lack of information he had been given. In other words, he had no idea of the maelstrom he was to walk into. Militant Mau Mau activity against British collaborators began in 1949, but the Kenyan Revolutionary War only really erupted into a full-blown insurgency after 1952. The first European to be killed by the Mau Mau was a British woman stabbed to death in the streets near her home in Thika on 3 October 1952. 6 days later, Senior Chief Waruhiu, one of the strongest supporters of the British administration, was shot to death in his car in broad daylight. Waruhiu's assassination finally convinced the Colonial Office to allow Baring to declare a State of Emergency.

The State of Emergency was declared on the night of the 20th October. That night and the following morning, Operation Jock Scott was mounted, a sweep intended to capture the leadership of the Mau Mau, thereby decapitating the movement. The details of the Operation were leaked by Africans within the police force, however, and whilst the moderate nationalist leaders sat patiently, awaiting capture, the more militant nationalists such as Dedan Kemathi and Stanley Mathenge fled into the forests. On the 22nd of October, loyalist chief Nderi was found hacked to pieces and a series of gruesome murders were perpetrated against settlers in the following months. It remains to this day uncertain whether these murders were committed by the Mau Mau, whether they had approval for the leadership and whether they were part of a concerted campaign to terrorise the European population. Reprisals by African loyalist forces alienated many moderate Gĩkũyũ, driving them into the arms of the Mau Mau militants, whose ranks swelled.

To combat the increasing aggressiveness of the Mau Mau attacks, the British authorities strengthened their forces. 3 King's African Rifles battalions were recalled from Tanganyika, Uganda and Mauritius. Combined with the existing African loyalist forces, the British commanded 3,000 African troops in Kenya. Fearful of being dependent on Black Africans for their security, the White settlers in Kenya demanded ethnically English troops. To placate the settlers, a battalion of Lancashire Fusiliers were flown in from the Middle East on the day the State of Emergency was declared. In November, Governor Baring sought assistance from the Security Service (MI5). A.M. MacDonald was sent, and would reorganise the Special Branch of the Kenya Police.

In January 1953, half-a-dozen notable nationalists, the "Kapenguria Six" (Bildad Kaggia, Kung'u Karumba, Jomo Kenyatta, Fred Kubai, Paul Ngei and Achieng' Oneko) were subject to a show trial. The case was extremely flimsy, but the Six were imprisoned nevertheless. Most historians agree that the trial was due to pressure from London to justify the use of military force in Kenya, as well as evidence of success through the imprisonment of significant nationalists.

At the declaration of the State of Emergency, hundreds (and later thousands) of Mau Mau fled to the forests, where a decentralised leadership had begun to set up platoons. Their primary initial zones of control were the Aberdares and the forest around Mount Kenya, whilst a passive support wing was fostered in other areas, especially Nairobi. In May 1953, General Baron Bourne was sent to Kenya to oversee restoration of order in the colony[58]. Bourne's background in artillery led him to promote a doctrine of creep-and-fire tactics, where areas suspected to contain Mau Mau were bombarded, then occupied by land forces. Although the use of artillery was effective at repelling frontal attacks by large groups of Mau Mau, this was a rare occurence. More often, the Mau Mau would use the bombardment delay to escape.

In order to deny financial and other support assets to the Mau Mau, the British attempted to isolate the Mau Mau's urban supporters from the armies in the countryside. To achieve this, the British launched on the 24 April 1954 Operation Anvil, a Nairobi-wide sweep to purge the city of Mau Mau supporters. Nairobi was sealed off and over 20,000 members of the British security forces (out of 56,000 troops overall) performed a sector-by-sector program of arrests. All African residents were taken to barbed-wire enclosures, where Africans of non-Gĩkũyũ, Embu or Amîîrú ethnicity were released. Male suspects were detained, whilst women and children were sent to reserves in the countryside. By the end of the operation, 20,000 men had been sent to Lang'ata, whilst 20,000 Africans were sent to reserves.

The major breakthroughs for the Mau Mau occurred in 1955, when the insurgency spread into the lands of other ethnic groups. In March, several Mau Mau units were chased into the lands of the ŋiTurkana, Nandi, Kalenjin and Loikop. British forces launched reprisal attacks on the local peoples, based on the unproven belief that they were sheltering Mau Mau [59]. The indiscriminate killings led many of these neutral peoples to take arms against the British. The expansion of the war against the Mau Mau overstretched the British forces at a time where the United Kingdom was already distracted elsewhere, particularly by events in the Middle East. The British increasingly ceded de-facto control of the countryside to the Mau Mau, who vastly outnumbered them. Although they continued to mount occasional large patrols, they were unable to cut the Mau Mau completely off of the populations which assisted them. Although African loyalist forces participated in the destruction of several villages, these terror tactics merely pushed more Africans to support of the anti-colonial forces. In reaction to the inability of the British to pacify the Africans and the increasing frequency of Mau Mau raids on the outskirts of the cities and the brutal murders of white farmers, the White Kenyan population started to mobilise part of their male adult populations into 'self-defence forces', vigilante posses that lynched Africans in urban centres suspected of assisting the Mau Mau. Occasionally, they even launched attacks on Gĩkũyũ villages in the vicinity of Nairobi. Small forces of South African and Rhodesian soldiers were also sent by their respective governments to assist the Kenyan Whites.

LCpl. Western was puffing on his cigarette when his ear caught the sound of a twig snapping in the darkness. His men were guarding the outer perimeter of the Rhodesian camp on the South Island of Lake Rudolf. This was their base of operations for tomorrow's offensive against the Turkana. There was nothing particularly concerning about the sound. It would just be another animal. Western had practically grown up in the bush, and he had learnt as a boy that there was more to worry about out here if there was no sound. Animals make a lot of noise. If it's too quiet, they're either dead, or afraid they're going to be. His men were no different, he supposed. Smythe and Tanner were troubling each other again. Usually it bugged him, but he didn't mind tonight. He felt right. He hadn't felt this relaxed since he'd been in this country. Then gunfire sounded from nearby. Nearby enough to hear it, but not right at that position. Western's men took up their rifles and got into defensive position, prepared for an assault from the outside. Nothing. "Smythe, go check out whats got the Southern line so jumpy". "Yessir". Smythe jogged out to the darkness in the South. After a minute or so, he called out in pain. "What the fuck!?" the men stood bolt upright. "Alright, lets get moving!" Western barked. Just as they were about to go and search for Smythe, shrieks were heard from the darkness. Turkana war cries. "Faaaaack!" Tanner called out as red cloth appeared out of the darkness. The Turkana warriors were upon their position in no time. Western grabbed his pump-action shotgun and put down one, then two, three. He heard a gargling sound behind him. Western spun around to see Tanner impaled from behind by a spear, with a Turkana warrior grimacing menacingly as he pulled the spear free. At the same moment the Turkana warrior threw his spear, Western let off one final shot with his shotgun, sending the limp body of the Turkana warrior spinning into the back wall of the makeshift fortification. Western barely felt the spear penetrate his chest until he was knocked onto his back by the weight of the missile. He felt the searing pain as his adrenaline flowed away, along with the blood he began to cough up. The din of battle in the background grew ever fainter. His sight faded, and he couldn't discern the outline of the Turkana standing over him. He merely saw two eyes in the darkness, as well as the flash that ended his life.

The military situation for the British became increasingly untenable through 1955 and 1956. By 1957, White farmers were abandoning their farms en masse, fleeing to the relatively safety of Nairobi and Mombasa. The Mau Mau militias had become larger and bolder. In November 1956, Mau Mau forces overran the prison in Lodwar. Jomo Kenyatta, Paul Ngei and Achieng Oneko were summarily executed. Bildad Kaggia was treated with reverence and respect by the Mau Mau rebels that took the prison, showing the connection Kaggia had with radicals in Kenya even prior to the end of colonial rule[60]. In July, an ambitious Mau Mau attack on Nairobi floundered, largely due to the lack of coordination arising from rivalries between Mau Mau leaders Stanley Mathenge and Dedan Kimathi. The subsequent panic in the capital led to a mass movement of White Kenyans from Nairobi to Mombasa, prepared to evacuate as pressure mounted from the anti-colonialists. Almost the entirety of British and Commonwealth forces in the country were deployed protecting the evacuees from possible attack in their migration to the coast. RAF assets bombed Mau Mau units that dared to approach. In the next few months, Mau Mau forces made incremental advances through the outer suburbs of Nairobi, finally capturing the city centre in December. The South African troops defending the city withdrew, whilst a force of White Kenyan militiamen fought a valiant, if futile rearguard action against the Mau Mau. Several were flayed alive and dragged through the streets by Kimathi's forces [61].

Upon hearing of the fall of Nairobi, European colonists boarded Royal Navy ships in the port of Mombasa, where they were taken to Tanganyika and housed in refugee camps. The government of the Central African Federation offered to take in the White Kenyans, the majority of whom accepted the offer. Those that didn't left for Canada, the United Kingdom and New Zealand. A small number remained in Tanganyika. Whilst much of the European population was saved from retribution, Asian Kenyans were not so lucky. Shopkeepers were dragged out of their homes, mercilessly tortured and killed. Women and girls were raped on a large scale. The exception was the group that were smuggled out of the country by prominent Asian lawyer A.R. Kapila. Having unsuccessfully defended Kaggia and the rest of the Kapenguria Six, he was allowed to leave with several other skilled Asians, who fled to the Seychelles, Tanganyika and the United Kingdom.

In panic and hoping to contain the sentiment of anti-colonialism spreading throughout the African parts of the Empire, the British government entered immediately into negotiations with the Mau Mau leaders.

[58]IOTL, Gen. George Erskine was brought in. His doctrine was more mobile (and effective). Using Erskine's tactics, the British forces were able to capture Waruhiu Itote (General China), one of the major Mau Mau commanders. This also improved the British access to intel.

[59] This did not occur IOTL. Whilst many of the ethnic groups of Kenya were unhappy with British colonial rule, relatively few took part in active fighting. The reasons for this I'm not sure, but the ŋiTurkana lands were a 'closed district'. The British were concerned about possible ŋiTurkana participation in resistance to colonialism, as they were apparently fearsome warriors.

[60] This event also did not occur. Lodwar is in ŋiTurkana lands and was therefore never around fighting during the rebellion.

[61] In OTL, the Mau Mau were defeated through the use of widespread villagisation programs. These did not occur ITTL due to the absence of JC Carothers, who formulated the program in Kenya.

Challenges to British colonial rule in Kenya developed in the immediate post-war period, coming to a head in the 1950s with the so-called Mau Mau Rebellion. To understand this rebellion, as with most major civil conflicts, we must examine the structure of colonial society in British Kenya and the manner in which it marginalised the native peoples.

The native population of the colony was divided between a variety of ethnic groups of both Bantu and Nilotic origin. The main Bantu groups were the Gĩkũyũ (Kikuyu), Amîîrú (Meru), AbaGusii (Kisii), Embu, Wakamba (Akamba), Abaluyia (Luhya), Waswahili (Swahili) and Mijikenda peoples. Major Nilotic groups included the Joluo (Luo), Maasai (Masai), ŋiTurkana (Turkana), Loikop (Samburu) and Kalenjin. The largest of these were the Gĩkũyũ and the Joluo.

The largest ethnic group in British Kenya (and the primary contributors to the Mau Mau forces) were the Gĩkũyũ, whose homeland lay in the Western foothills of Mount Kenya, known to the Gĩkũyũ as Kĩrĩ Nyaga (where God lives). The 1939 White Highlands Order expelled natives (largely Gĩkũyũ) from hill farms reserved for European settlement and known as "the White Highlands". Although native dispossession and European (largely British) settlement in the Highlands had been ongoing for several decades, large native populations remained in the role of farmhands, living on their ancestral land with the permission of their employers. As mechanisation reached colonial Kenya from Britain in the 1930s, however, the demand for cheap manual labour lessened dramatically. Remaining native squatters were subjected to oppressive labour contracts and the colonial administration also limited the number of livestock individual Gĩkũyũ could own. The limitations on native property instituted by the colonial administration created significant pressure on a society which highly valued land ownership and used cattle as currency.

These pressures established a social dimension to what is often considered in the West to have been an anti-colonial struggle between monolithic native and British blocs. The limitation of grazing to defined native reserves placed stress on finite (and often comparatively poor, compared to those in the White Highlands) resources. Those most severely affected by the new legislation were the landless men ("ahoi") and guest residents ("jodak"). Founder lineages within Gĩkũyũ society increasingly sought total control over property they claimed to be theirs. Aware of the pressures on Gĩkũyũ society, the colonial administration tried to improve productivity of native reservations through the introduction of bench-terracing to increase agricultural yields. Whilst this policy seemed applaudable, this particular policy was viewed with suspicion by the natives. It did increase demand for manual labour again, but natives were often coerced into working and purposely put up resistance to the works. The Joluo people in particular were staunchly opposed, fearing (like many other natives) that the British were merely trying to garner support and intended to confiscate the hills once they were made productive.

Adding to the rapidly changing social environment within native society were the "keya", African soldiers returning from service in WWII. These keya brought back with them valuable capital which they invested in small businesses, such as shops, tea-rooms, water-mills, lorries and buses. The increasing importance of keya in Gĩkũyũ society brought them into conflict with traditional social forces, namely the chiefly and "karani" (cleric) class. This tension has been characterised by Marxist analysts as a contest between "progressive" urban keya and "reactionary" rural chiefs/karani. The most severe tension, however, was between the natives and the (South) Asian traders which were the primary competitors with the emerging native entrepeneurs who wanted to establish an independent native middle-class, as opposed to the Asian middle class that relied on colonial patronage.

Given restrictions on African political activity, there were only two avenues available to political representation of the African entrepeneurs: the Kenya African Union (KAU) or collaboration with the colonial government. Those that joined the KAU tended towards moderate nationalism, siding with the like of Jomo Kenyatta. They therefore played very little active role in the Mau Mau Rebellion itself, although they would be profoundly impacted by the social restructuring afterwards. Nevertheless, Kenyans of all social standings experienced similar discrimination in the segregated colonial society. In the capital, Nairobi, and other major cities such as Malindi and Lamu, European settlers lived separately from the African population. A formal colour bar excluded natives from access to sanitary urban housing, wages, adequate schooling and infrastructural support. Urban opportunities were few, with very limited licenses for African traders and the largest employers offering little more than manual dock labour to Africans.

Sir Philip Euen Mitchell was the Governor of British Kenya between 1944 and the summer of 1952, when he retired. Mitchell had taken a very light stance on the Mau Mau forces which had started to attack African collaborators. These attacks were dismissed by Mitchell as isolated incidents, not as part of a wider politico-military campaign. Mitchell was replaced by Henry Potter, who for a short period was Acting Governor. The Colonial Office received regular reports from Potter about escalating Mau Mau violence, but it wasn't until late 1953 that the Colonial Office recognised the seriousness of the rebellion.

On 30 September 1952, Sir Evelyn Baring, son of the first British governor of Egypt, replaced Potter permanently. Baring was forced to proverbially "hit-the-ground-running" due to the lack of information he had been given. In other words, he had no idea of the maelstrom he was to walk into. Militant Mau Mau activity against British collaborators began in 1949, but the Kenyan Revolutionary War only really erupted into a full-blown insurgency after 1952. The first European to be killed by the Mau Mau was a British woman stabbed to death in the streets near her home in Thika on 3 October 1952. 6 days later, Senior Chief Waruhiu, one of the strongest supporters of the British administration, was shot to death in his car in broad daylight. Waruhiu's assassination finally convinced the Colonial Office to allow Baring to declare a State of Emergency.

The State of Emergency was declared on the night of the 20th October. That night and the following morning, Operation Jock Scott was mounted, a sweep intended to capture the leadership of the Mau Mau, thereby decapitating the movement. The details of the Operation were leaked by Africans within the police force, however, and whilst the moderate nationalist leaders sat patiently, awaiting capture, the more militant nationalists such as Dedan Kemathi and Stanley Mathenge fled into the forests. On the 22nd of October, loyalist chief Nderi was found hacked to pieces and a series of gruesome murders were perpetrated against settlers in the following months. It remains to this day uncertain whether these murders were committed by the Mau Mau, whether they had approval for the leadership and whether they were part of a concerted campaign to terrorise the European population. Reprisals by African loyalist forces alienated many moderate Gĩkũyũ, driving them into the arms of the Mau Mau militants, whose ranks swelled.

To combat the increasing aggressiveness of the Mau Mau attacks, the British authorities strengthened their forces. 3 King's African Rifles battalions were recalled from Tanganyika, Uganda and Mauritius. Combined with the existing African loyalist forces, the British commanded 3,000 African troops in Kenya. Fearful of being dependent on Black Africans for their security, the White settlers in Kenya demanded ethnically English troops. To placate the settlers, a battalion of Lancashire Fusiliers were flown in from the Middle East on the day the State of Emergency was declared. In November, Governor Baring sought assistance from the Security Service (MI5). A.M. MacDonald was sent, and would reorganise the Special Branch of the Kenya Police.

In January 1953, half-a-dozen notable nationalists, the "Kapenguria Six" (Bildad Kaggia, Kung'u Karumba, Jomo Kenyatta, Fred Kubai, Paul Ngei and Achieng' Oneko) were subject to a show trial. The case was extremely flimsy, but the Six were imprisoned nevertheless. Most historians agree that the trial was due to pressure from London to justify the use of military force in Kenya, as well as evidence of success through the imprisonment of significant nationalists.

At the declaration of the State of Emergency, hundreds (and later thousands) of Mau Mau fled to the forests, where a decentralised leadership had begun to set up platoons. Their primary initial zones of control were the Aberdares and the forest around Mount Kenya, whilst a passive support wing was fostered in other areas, especially Nairobi. In May 1953, General Baron Bourne was sent to Kenya to oversee restoration of order in the colony[58]. Bourne's background in artillery led him to promote a doctrine of creep-and-fire tactics, where areas suspected to contain Mau Mau were bombarded, then occupied by land forces. Although the use of artillery was effective at repelling frontal attacks by large groups of Mau Mau, this was a rare occurence. More often, the Mau Mau would use the bombardment delay to escape.

In order to deny financial and other support assets to the Mau Mau, the British attempted to isolate the Mau Mau's urban supporters from the armies in the countryside. To achieve this, the British launched on the 24 April 1954 Operation Anvil, a Nairobi-wide sweep to purge the city of Mau Mau supporters. Nairobi was sealed off and over 20,000 members of the British security forces (out of 56,000 troops overall) performed a sector-by-sector program of arrests. All African residents were taken to barbed-wire enclosures, where Africans of non-Gĩkũyũ, Embu or Amîîrú ethnicity were released. Male suspects were detained, whilst women and children were sent to reserves in the countryside. By the end of the operation, 20,000 men had been sent to Lang'ata, whilst 20,000 Africans were sent to reserves.

The major breakthroughs for the Mau Mau occurred in 1955, when the insurgency spread into the lands of other ethnic groups. In March, several Mau Mau units were chased into the lands of the ŋiTurkana, Nandi, Kalenjin and Loikop. British forces launched reprisal attacks on the local peoples, based on the unproven belief that they were sheltering Mau Mau [59]. The indiscriminate killings led many of these neutral peoples to take arms against the British. The expansion of the war against the Mau Mau overstretched the British forces at a time where the United Kingdom was already distracted elsewhere, particularly by events in the Middle East. The British increasingly ceded de-facto control of the countryside to the Mau Mau, who vastly outnumbered them. Although they continued to mount occasional large patrols, they were unable to cut the Mau Mau completely off of the populations which assisted them. Although African loyalist forces participated in the destruction of several villages, these terror tactics merely pushed more Africans to support of the anti-colonial forces. In reaction to the inability of the British to pacify the Africans and the increasing frequency of Mau Mau raids on the outskirts of the cities and the brutal murders of white farmers, the White Kenyan population started to mobilise part of their male adult populations into 'self-defence forces', vigilante posses that lynched Africans in urban centres suspected of assisting the Mau Mau. Occasionally, they even launched attacks on Gĩkũyũ villages in the vicinity of Nairobi. Small forces of South African and Rhodesian soldiers were also sent by their respective governments to assist the Kenyan Whites.

LCpl. Western was puffing on his cigarette when his ear caught the sound of a twig snapping in the darkness. His men were guarding the outer perimeter of the Rhodesian camp on the South Island of Lake Rudolf. This was their base of operations for tomorrow's offensive against the Turkana. There was nothing particularly concerning about the sound. It would just be another animal. Western had practically grown up in the bush, and he had learnt as a boy that there was more to worry about out here if there was no sound. Animals make a lot of noise. If it's too quiet, they're either dead, or afraid they're going to be. His men were no different, he supposed. Smythe and Tanner were troubling each other again. Usually it bugged him, but he didn't mind tonight. He felt right. He hadn't felt this relaxed since he'd been in this country. Then gunfire sounded from nearby. Nearby enough to hear it, but not right at that position. Western's men took up their rifles and got into defensive position, prepared for an assault from the outside. Nothing. "Smythe, go check out whats got the Southern line so jumpy". "Yessir". Smythe jogged out to the darkness in the South. After a minute or so, he called out in pain. "What the fuck!?" the men stood bolt upright. "Alright, lets get moving!" Western barked. Just as they were about to go and search for Smythe, shrieks were heard from the darkness. Turkana war cries. "Faaaaack!" Tanner called out as red cloth appeared out of the darkness. The Turkana warriors were upon their position in no time. Western grabbed his pump-action shotgun and put down one, then two, three. He heard a gargling sound behind him. Western spun around to see Tanner impaled from behind by a spear, with a Turkana warrior grimacing menacingly as he pulled the spear free. At the same moment the Turkana warrior threw his spear, Western let off one final shot with his shotgun, sending the limp body of the Turkana warrior spinning into the back wall of the makeshift fortification. Western barely felt the spear penetrate his chest until he was knocked onto his back by the weight of the missile. He felt the searing pain as his adrenaline flowed away, along with the blood he began to cough up. The din of battle in the background grew ever fainter. His sight faded, and he couldn't discern the outline of the Turkana standing over him. He merely saw two eyes in the darkness, as well as the flash that ended his life.

The military situation for the British became increasingly untenable through 1955 and 1956. By 1957, White farmers were abandoning their farms en masse, fleeing to the relatively safety of Nairobi and Mombasa. The Mau Mau militias had become larger and bolder. In November 1956, Mau Mau forces overran the prison in Lodwar. Jomo Kenyatta, Paul Ngei and Achieng Oneko were summarily executed. Bildad Kaggia was treated with reverence and respect by the Mau Mau rebels that took the prison, showing the connection Kaggia had with radicals in Kenya even prior to the end of colonial rule[60]. In July, an ambitious Mau Mau attack on Nairobi floundered, largely due to the lack of coordination arising from rivalries between Mau Mau leaders Stanley Mathenge and Dedan Kimathi. The subsequent panic in the capital led to a mass movement of White Kenyans from Nairobi to Mombasa, prepared to evacuate as pressure mounted from the anti-colonialists. Almost the entirety of British and Commonwealth forces in the country were deployed protecting the evacuees from possible attack in their migration to the coast. RAF assets bombed Mau Mau units that dared to approach. In the next few months, Mau Mau forces made incremental advances through the outer suburbs of Nairobi, finally capturing the city centre in December. The South African troops defending the city withdrew, whilst a force of White Kenyan militiamen fought a valiant, if futile rearguard action against the Mau Mau. Several were flayed alive and dragged through the streets by Kimathi's forces [61].

Upon hearing of the fall of Nairobi, European colonists boarded Royal Navy ships in the port of Mombasa, where they were taken to Tanganyika and housed in refugee camps. The government of the Central African Federation offered to take in the White Kenyans, the majority of whom accepted the offer. Those that didn't left for Canada, the United Kingdom and New Zealand. A small number remained in Tanganyika. Whilst much of the European population was saved from retribution, Asian Kenyans were not so lucky. Shopkeepers were dragged out of their homes, mercilessly tortured and killed. Women and girls were raped on a large scale. The exception was the group that were smuggled out of the country by prominent Asian lawyer A.R. Kapila. Having unsuccessfully defended Kaggia and the rest of the Kapenguria Six, he was allowed to leave with several other skilled Asians, who fled to the Seychelles, Tanganyika and the United Kingdom.

In panic and hoping to contain the sentiment of anti-colonialism spreading throughout the African parts of the Empire, the British government entered immediately into negotiations with the Mau Mau leaders.

[58]IOTL, Gen. George Erskine was brought in. His doctrine was more mobile (and effective). Using Erskine's tactics, the British forces were able to capture Waruhiu Itote (General China), one of the major Mau Mau commanders. This also improved the British access to intel.

[59] This did not occur IOTL. Whilst many of the ethnic groups of Kenya were unhappy with British colonial rule, relatively few took part in active fighting. The reasons for this I'm not sure, but the ŋiTurkana lands were a 'closed district'. The British were concerned about possible ŋiTurkana participation in resistance to colonialism, as they were apparently fearsome warriors.

[60] This event also did not occur. Lodwar is in ŋiTurkana lands and was therefore never around fighting during the rebellion.

[61] In OTL, the Mau Mau were defeated through the use of widespread villagisation programs. These did not occur ITTL due to the absence of JC Carothers, who formulated the program in Kenya.

Last edited:

GiantMonkeyMan

Banned

Very interesting. There's this assumption I believe that the decolonisation period for Britain was peaceful and successful whereas the reality was completely different and could have turned out much like you've laid out ITL. The beginning of the escalation reminds me of a bit of Fanon's The Wretched of the Earth:

The accumulated, exacerbated hate explodes. The neighbouring police barracks is captured, the policemen are hacked to pieces, the local schoolmaster is murdered, the doctor only gets away with his life because he was not at home, etc. Pacifying forces are hurried to the spot and the air-force bombards it. Then the banner of revolt is unfurled, the old warrior-like traditions spring up again, the women cheer, the men organise and take up positions in the mountains, and guerrilla war begins. The peasantry spontaneously gives concrete form to the general insecurity; and colonialism takes fright and either continues the war or negotiates.

The accumulated, exacerbated hate explodes. The neighbouring police barracks is captured, the policemen are hacked to pieces, the local schoolmaster is murdered, the doctor only gets away with his life because he was not at home, etc. Pacifying forces are hurried to the spot and the air-force bombards it. Then the banner of revolt is unfurled, the old warrior-like traditions spring up again, the women cheer, the men organise and take up positions in the mountains, and guerrilla war begins. The peasantry spontaneously gives concrete form to the general insecurity; and colonialism takes fright and either continues the war or negotiates.

Very interesting. There's this assumption I believe that the decolonisation period for Britain was peaceful and successful whereas the reality was completely different and could have turned out much like you've laid out ITL. The beginning of the escalation reminds me of a bit of Fanon's The Wretched of the Earth:

The accumulated, exacerbated hate explodes. The neighbouring police barracks is captured, the policemen are hacked to pieces, the local schoolmaster is murdered, the doctor only gets away with his life because he was not at home, etc. Pacifying forces are hurried to the spot and the air-force bombards it. Then the banner of revolt is unfurled, the old warrior-like traditions spring up again, the women cheer, the men organise and take up positions in the mountains, and guerrilla war begins. The peasantry spontaneously gives concrete form to the general insecurity; and colonialism takes fright and either continues the war or negotiates.

That's REALLY good. I haven't actually read Fanon, but it sounds very interesting! I did find that its really interesting to explore what the world would've been like if more of the militant anti-colonial movements were more successful, as opposed to a lot of (relatively) moderate ones that were successful like Kenyatta's movement in Kenya. There will be a second part about Kenya, I'm just still working out how the country will turn out post-Mau Mau. I've got some ideas but I haven't absolutely decided yet.

GiantMonkeyMan

Banned

The Wretched of the Earth is fantastic, I would totally recommend it if only to get into the mindset of the native during the decolonisation period. Fanon was a psychologist who treated both colonial police and administrators as well as the native resistance fighters during the Algerian War of Independence and there's a section in the book where he describes some of the common examples of mental scarring that independence wars inflict on the people involved. He's also a great writer with gems like this: Everybody will have to be compromised in the fight for the common good. No one has clean hands; there are no innocents and onlookers. We all have dirty hands; we are soiling them in the swamps of our country and in the terrifying emptiness of our brains. Every onlooker is either a coward or a traitor.That's REALLY good. I haven't actually read Fanon, but it sounds very interesting! I did find that its really interesting to explore what the world would've been like if more of the militant anti-colonial movements were more successful, as opposed to a lot of (relatively) moderate ones that were successful like Kenyatta's movement in Kenya. There will be a second part about Kenya, I'm just still working out how the country will turn out post-Mau Mau. I've got some ideas but I haven't absolutely decided yet.

Anyway, you've already identified what I would believe to be the main source of conflict in the post-colonial period. Namely between the emerging native middle class who would most likely be nationalists and the tribal chiefs who would be more federalist, vying for power for their own particular ethnic grouping. Your whole timeline is interesting and I'm looking forward to more.

I was actually thinking about that the other day. I will include one in the next few updates, but I really need to do some more research to give it the love it deserves. Any ideas for the update or sources that're useful?

Sice India and Pakistan are already separate, then we can have the British and the Americans helping India with a Soviet supported China and a China supported Pakistan.

Since India and Pakistan are already separate, then we can have the British and the Americans helping India with a Soviet supported China and a China supported Pakistan.

But wasn't India pro-Soviet whilst Pakistan was pro-American? I'll likely have Pakistan continue to be anti-Soviet due to the USSR's official policy of atheism. Pakistan will be aligned with Hyderabad, both of which will be anti-Indian. But I'll do more research and get an update on the Indian Subcontinent done eventually. I'd rather do a lot of research and make a post than just make one ASAP. India does tend to get ignored on this board, unfortunately, and I don't want to be just another TL author that glosses over it. That said, research is necessary given that I don't know much about the subcontinent.

Anyway, you've already identified what I would believe to be the main source of conflict in the post-colonial period. Namely between the emerging native middle class who would most likely be nationalists and the tribal chiefs who would be more federalist, vying for power for their own particular ethnic grouping. Your whole timeline is interesting and I'm looking forward to more.

I will be absolutely certain to check out The Wretched of the Earth, particularly as I have yet to do an update on Algeria (which is one of the elephants in the room for the 1950s).

I really appreciate your, well, appreciation for the timeline, its good to know people are enjoying it

But wasn't India pro-Soviet whilst Pakistan was pro-American? I'll likely have Pakistan continue to be anti-Soviet due to the USSR's official policy of atheism. Pakistan will be aligned with Hyderabad, both of which will be anti-Indian. But I'll do more research and get an update on the Indian Subcontinent done eventually. I'd rather do a lot of research and make a post than just make one ASAP. India does tend to get ignored on this board, unfortunately, and I don't want to be just another TL author that glosses over it. That said, research is necessary given that I don't know much about the subcontinent.

Hyderabad had very little chance of remaining independant actually. It was surrounded by India on all sides and had a majority Hindu population.

Hyderabad had very little chance of remaining independant actually. It was surrounded by India on all sides and had a majority Hindu population.

Exactly, hence the need to find a plausible way to keep it alive!

You could amend it slightly. India wasn't exactly Pro-Soviet as much as it was Anti-Pakistani. Plus with tensions between China and India over the borders, I guess they felt that they needed a "Big Mate" to look after them seeing as Britain was no longer up to the job. With the US supporting Pakistan and Russia looking for allies against the Chinese, it was a no-brainer.

Despite everything, I still think there is quite an Anglophile feel to India.

Despite everything, I still think there is quite an Anglophile feel to India.

You could amend it slightly. India wasn't exactly Pro-Soviet as much as it was Anti-Pakistani. Plus with tensions between China and India over the borders, I guess they felt that they needed a "Big Mate" to look after them seeing as Britain was no longer up to the job. With the US supporting Pakistan and Russia looking for allies against the Chinese, it was a no-brainer.

Despite everything, I still think there is quite an Anglophile feel to India.

I'm definitely going to have to reverse the clock a little bit with India, like I did with the Yugoslavia update. I think I may have come across some info that could lead to a plausible separation between India and Hyderabad, but much more research on the topic is still needed. I feel like I'm going to have to read quite a bit about the partition and the major figures in India's genesis, like Mountbatten, Nehru, Gandhi, Patel, Bose etc. (some help with Pakistanis to search up would be useful too).

I don't think that the sentiments in particular in India were anglophile, I think it's just that they retained a lot of institutions from the British ("if it ain't broke, don't fix it" attitude), rather than actually being pro-British.

Chapter 18b: Uhuru and the Divergence of Destinies - Kenyan Decolonisation (1950s)

A New World (1950s): Uhuru and the Divergence of Destinies (Kenya Pt.2)

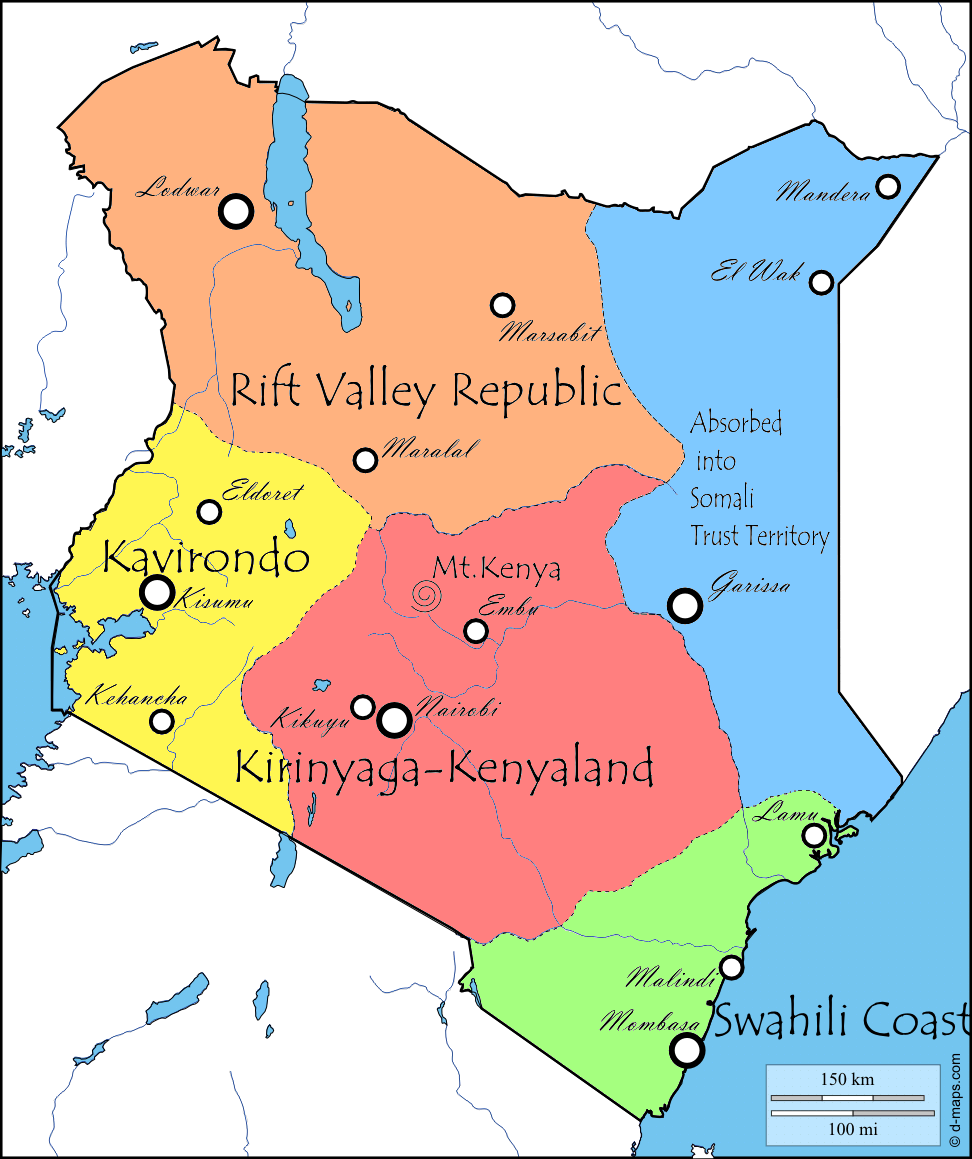

Although initial negotiations between the Mau Mau leaders and the British appeared to be moving towards the granting of independence (Uhuru) of Kenya, the integrity of the theorised native Kenyan state was undermined by the events immediately following the British retreat.

Without the British presence to oppose, the various Mau Mau militia in the centre of the country began to turn on each other. The two factions that developed had significantly different views of Kenya's future. The faction led by Bildad Kaggia (with Dedan Kimathi) promoted radical social reconstruction and land redistribution, whilst shedding traditional beliefs in favour of accelerated nation-building for a united Kenya. The second faction, led by Stanley Mathenge and supported by Waruhiu Itote and Musa Mwariama supported traditional beliefs and the development of an authentic Africa culture, unsullied by eurocentric political beliefs. Longstanding tensions between Kimathi and Mathenge that had become particularly apparent during the siege of Nairobi contributed to the development of the conflict between the two factions. The two factions separated officially into political parties, with the Kaggia-Kimathi faction becoming the Kenya Peoples' Popular Front (KPPF) and the Mathenge-Itote-Mwariama triumvirate forming the Kirinyaga National Union (KNU) [62].

Tensions between the KPPF and the KNU came to a fore in November 1957. On the 23rd, KNU forces ambushed KPPF militia to the south of Embu Town. 3 KNU and 7 KPPF militiamen were killed in a skirmish. Although a seemingly unimportant incident, the skirmish marked the onset of a conflict known variously as the Kenyan Civil War or the intra-Kirinyaga Conflicts. The KNU and KPPF conflicts also provided an impetus for the balkanisation of Kenya. Despite the majority of the fighting taking place within the lands of the Embu, Kikuyu and Meru, the KPPF engaged in raids against the Mijikenda peoples to the East and the Kalenjin to the West. This spurred the creation of regional alliances which coalesced into states. In the western Great Lakes region, the Luo, Luhya and Kalenjin peoples collectively formed the Kingdom of Kavirondo in June 1958. Kavirondo is notable in that it is an elective monarchy. This arose from a tradition within the Luo people of titling notable peoples as 'king' or 'ker'. The first ruler of Kavirondo was Ker Oginga Odinga, the founder of the Luo Thrift and Trading Corporation. The large population size of Kavirondo kept it safe from immediate intervention by Kirinyaga-Kenyaland after the cessation of the Kirinyaga Conflicts, although the new state foudn an immediate challenge in the rapid growth of unorthodox religious movements, particularly the Legio Maria led by Melkio Ondetto (the Lodvikus or Son of God), which had split off of the official Catholic church.

The withdrawal of the British had led to a complete absence of outside authority in the lands of the ŋiTurkana to the west of Lake Rudolf. The neighbouring Loikop, Rendille and Oromo peoples united with the ŋiTurkana, partially out of concern that the warriors of the ŋiTurkana would forcibly take land and cattle. At least with this arrangement, argued the Loikop and Rendille chiefs, they would be able to retain some autonomy. The Oromo people were the most loosely incorporated into the resulting state, known as the Rift Valley Republic. The Oromo valued membership in the Republic as a manner to gaining support for the annexation of areas of mixed Somali and Oromo habitation.

In response to the danger of Oromo attacks on Somali settlements, the Italian-administered Trust Territory of Somalia intervened with UN acquiescence by expanding its authority over the North-Eastern territories in March 1959. These areas were inhabited largely by Somalis. This move was supported by the local Somalis, overjoyed both at the protection provided and the ability to increase ties with their clan-brothers who had formerly been divided from them by an arbitrary border.

Whilst the KNU and KPPF pursued their war in the centre of the country, conflict arose between the Maasai of the south and their AbaGusii neighbours. The AbaGusii faced significant problems of overpopulation, whilst the Maasai pastoralists had a very low population density for their area of occupation. The breakdown of state cohesion led to the mounting of an AbaGusii campaign of genocide against the Maasai people. Unable to match the AbaGusii numerically, the Maasai were killed en masse. The genocide was halted only by the intervention of KPPF forces which halted the AbaGusii. To prevent a reprisal campaign against them, the AbaGusii joined the Kingdom of Kavirondo, still occupying some of the land stolen off of the Maasai. Unwilling to clash with Kavirondo before defeating the KNU, the KPPF halted their advances. Nevertheless, the Maasai showed their thanks by loyally aligning themselves with the KPPF.

The KPPF raids against the Mijikenda concerned not only the Mijikenda, but also the Swahili peoples of the coast. The cities on the coast were relatively stable compared to the rest of the state, governing themselves independently. Despite this autonomy, the Swahili political elites were closely connected to each other and shared many of the same commercial interests. They were also fully aware of the certainty that the victor in the intra-Kirinyaga Conflicts would turn towards them first, as the wealthiest part of the country. The Mijikenda and Swahili peoples formed a confederation known as the Swahili Coast State.

In the event, the Civil War between the KPPF and KNU turned into a stalemate, and negotiations mediated by the British led to the establishment of the State of Kirinyaga-Kenyaland in the centre of Kenya. It was to be a semi-presidential republic, with the two warring factions becoming the main parties within the unicameral legislature. The British and Kirinyaga-Kenyaland also recognised the other new states and the incorporation of the North-East Territories to the Somali Trust Territories. Despite this, the KPPF always demanded the other territories of Kenya should be united under a socialist union. The balkanisation of Kenya was finalised in December 1959, only a short time before the mass decolonisation of Africa came into effect.

NOTE: Another interesting event of the balkanisation of Kenya was the discovery of the Kerit (also known as the Nandi Bear or Ngoloko), a hitherto legendary creature which was discovered in 1958 in Kavirondo. The discovery electrified the zoological world in the West, with scientists arriving from Europe, South Africa and the United States to research the creature. As it turns out, the kerit are a surviving population of prehistoric short-faced hyena (Pachycrocuta brevirostris). The kerit was adopted as the symbol of the Kavirondese kingship, and Ker Odinga famously kept one as a pet [63].

[62] Neither of these parties existed in OTL.

[63] The kerit may or may not exist. It hasn't been discovered, and as such it may exist. But, on the other hand, it may be legend. I went with the least outlandish explanation for it's origin.

Although initial negotiations between the Mau Mau leaders and the British appeared to be moving towards the granting of independence (Uhuru) of Kenya, the integrity of the theorised native Kenyan state was undermined by the events immediately following the British retreat.

Without the British presence to oppose, the various Mau Mau militia in the centre of the country began to turn on each other. The two factions that developed had significantly different views of Kenya's future. The faction led by Bildad Kaggia (with Dedan Kimathi) promoted radical social reconstruction and land redistribution, whilst shedding traditional beliefs in favour of accelerated nation-building for a united Kenya. The second faction, led by Stanley Mathenge and supported by Waruhiu Itote and Musa Mwariama supported traditional beliefs and the development of an authentic Africa culture, unsullied by eurocentric political beliefs. Longstanding tensions between Kimathi and Mathenge that had become particularly apparent during the siege of Nairobi contributed to the development of the conflict between the two factions. The two factions separated officially into political parties, with the Kaggia-Kimathi faction becoming the Kenya Peoples' Popular Front (KPPF) and the Mathenge-Itote-Mwariama triumvirate forming the Kirinyaga National Union (KNU) [62].

Tensions between the KPPF and the KNU came to a fore in November 1957. On the 23rd, KNU forces ambushed KPPF militia to the south of Embu Town. 3 KNU and 7 KPPF militiamen were killed in a skirmish. Although a seemingly unimportant incident, the skirmish marked the onset of a conflict known variously as the Kenyan Civil War or the intra-Kirinyaga Conflicts. The KNU and KPPF conflicts also provided an impetus for the balkanisation of Kenya. Despite the majority of the fighting taking place within the lands of the Embu, Kikuyu and Meru, the KPPF engaged in raids against the Mijikenda peoples to the East and the Kalenjin to the West. This spurred the creation of regional alliances which coalesced into states. In the western Great Lakes region, the Luo, Luhya and Kalenjin peoples collectively formed the Kingdom of Kavirondo in June 1958. Kavirondo is notable in that it is an elective monarchy. This arose from a tradition within the Luo people of titling notable peoples as 'king' or 'ker'. The first ruler of Kavirondo was Ker Oginga Odinga, the founder of the Luo Thrift and Trading Corporation. The large population size of Kavirondo kept it safe from immediate intervention by Kirinyaga-Kenyaland after the cessation of the Kirinyaga Conflicts, although the new state foudn an immediate challenge in the rapid growth of unorthodox religious movements, particularly the Legio Maria led by Melkio Ondetto (the Lodvikus or Son of God), which had split off of the official Catholic church.

The withdrawal of the British had led to a complete absence of outside authority in the lands of the ŋiTurkana to the west of Lake Rudolf. The neighbouring Loikop, Rendille and Oromo peoples united with the ŋiTurkana, partially out of concern that the warriors of the ŋiTurkana would forcibly take land and cattle. At least with this arrangement, argued the Loikop and Rendille chiefs, they would be able to retain some autonomy. The Oromo people were the most loosely incorporated into the resulting state, known as the Rift Valley Republic. The Oromo valued membership in the Republic as a manner to gaining support for the annexation of areas of mixed Somali and Oromo habitation.

In response to the danger of Oromo attacks on Somali settlements, the Italian-administered Trust Territory of Somalia intervened with UN acquiescence by expanding its authority over the North-Eastern territories in March 1959. These areas were inhabited largely by Somalis. This move was supported by the local Somalis, overjoyed both at the protection provided and the ability to increase ties with their clan-brothers who had formerly been divided from them by an arbitrary border.

Whilst the KNU and KPPF pursued their war in the centre of the country, conflict arose between the Maasai of the south and their AbaGusii neighbours. The AbaGusii faced significant problems of overpopulation, whilst the Maasai pastoralists had a very low population density for their area of occupation. The breakdown of state cohesion led to the mounting of an AbaGusii campaign of genocide against the Maasai people. Unable to match the AbaGusii numerically, the Maasai were killed en masse. The genocide was halted only by the intervention of KPPF forces which halted the AbaGusii. To prevent a reprisal campaign against them, the AbaGusii joined the Kingdom of Kavirondo, still occupying some of the land stolen off of the Maasai. Unwilling to clash with Kavirondo before defeating the KNU, the KPPF halted their advances. Nevertheless, the Maasai showed their thanks by loyally aligning themselves with the KPPF.

The KPPF raids against the Mijikenda concerned not only the Mijikenda, but also the Swahili peoples of the coast. The cities on the coast were relatively stable compared to the rest of the state, governing themselves independently. Despite this autonomy, the Swahili political elites were closely connected to each other and shared many of the same commercial interests. They were also fully aware of the certainty that the victor in the intra-Kirinyaga Conflicts would turn towards them first, as the wealthiest part of the country. The Mijikenda and Swahili peoples formed a confederation known as the Swahili Coast State.

In the event, the Civil War between the KPPF and KNU turned into a stalemate, and negotiations mediated by the British led to the establishment of the State of Kirinyaga-Kenyaland in the centre of Kenya. It was to be a semi-presidential republic, with the two warring factions becoming the main parties within the unicameral legislature. The British and Kirinyaga-Kenyaland also recognised the other new states and the incorporation of the North-East Territories to the Somali Trust Territories. Despite this, the KPPF always demanded the other territories of Kenya should be united under a socialist union. The balkanisation of Kenya was finalised in December 1959, only a short time before the mass decolonisation of Africa came into effect.

NOTE: Another interesting event of the balkanisation of Kenya was the discovery of the Kerit (also known as the Nandi Bear or Ngoloko), a hitherto legendary creature which was discovered in 1958 in Kavirondo. The discovery electrified the zoological world in the West, with scientists arriving from Europe, South Africa and the United States to research the creature. As it turns out, the kerit are a surviving population of prehistoric short-faced hyena (Pachycrocuta brevirostris). The kerit was adopted as the symbol of the Kavirondese kingship, and Ker Odinga famously kept one as a pet [63].

[62] Neither of these parties existed in OTL.

[63] The kerit may or may not exist. It hasn't been discovered, and as such it may exist. But, on the other hand, it may be legend. I went with the least outlandish explanation for it's origin.

Last edited:

FLAG OF THE SWAHILI COAST (Credit goes to Marc Pasquin)

FLAG OF THE RIFT VALLEY REPUBLIC (My own creation)

FLAG OF THE RIFT VALLEY REPUBLIC (My own creation)

*Bump* because I'm interested to hear readers' interpretations of a balkanised Kenya and any questions about the resulting states. Also want to hear opinions on perceived effects, resulting dynamics, economics etc.

Is Swahili Coast mostly Islamic? And I get the impression these states aren't going to be peaceful forever.

Is Swahili Coast mostly Islamic? And I get the impression these states aren't going to be peaceful forever.

Yes, the Swahili Coast is mostly Islamic, with Mijikenda traditional beliefs second most popular.

You're right, they aren't going to be peaceful forever, but the conflict I have planned for part of the region is largely going to be related to turmoil in neighbouring countries. (*cough* Ethiopia *cough*)

How does a certain Barack Obama (Barack Obama Sr.) fare ITTL?

I haven't really thought about it too much. So far I'm thinking that he'll study overseas, but in the UK, rather than the United States, which will butterfly away the existence of Barack Obama Jr. entirely. He will later return to Kavirondo where he will be a significant force in economics there.

Threadmarks

View all 122 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 98: The Conqueror? - Uganda (Until 1980) (Part 2) Chapter 99: Slaying the Beast - Uganda (Until 1980) (Part 3) Chapter 100 [SPECIAL] - Ad Astra - Aerospace Competition Between the Superpowers (Until 1980) (Part 1) Chapter 101 [SPECIAL] - Magnificent Desolation - Aerospace Competition Between the Superpowers (Until 1980) (Part 2) Chapter 102: Jadi Pandu Ibuku - Nusantara (Until 1980) Chapter 103: Furtive Seas - South Maluku and West Papua (Until 1980) Chapter 104: Kings and Kingmakers - Post-Independence North Kalimantan (Until 1980) Chapter 105: Maka-Diyos, Maka-Tao, Makakalikasan, at Makabansa - The Philippines (Until 1980)

Share: