don’t know how much to read into the fact that Immortal was never used

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Dread Nought but the Fury of the Seas

- Thread starter sts-200

- Start date

Surprisingly, all of the above never sank. I think we have a winner, ladies and gentlemen.HMS Immortalité - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

The story of HMS Immortalite really highlights just how dependent the RN was on French shipyards for it's ships and how generous the French were to keep donating ships.

While not really a Royal Navy name, I have to admit that I like the idea of HMS International, so that you can have everything that could/does go wrong with these ships happen to it and have it pick up the informal name of "The International Incident"

I like the idea of of one of them being named Inexhaustible since these ships are going to spend long periods of time travelling at high speeds to both scout and hunt down enemy crusers.

I like:

1. Imperious - aka 'I represent the Empire' - since she and her sisters are bound to be lauded as the RN's new 'look how great these are' ships;

2. Illustrious - same idea, 'look how great we are'

3. Implacable - "we're going ahead with our plans whether you like it or not"

and, I think my favourite for a peacetime ship...

4. Immaculate - let's face it, when not at war, sailors are kept busy by polishing, so she will be...

1. Imperious - aka 'I represent the Empire' - since she and her sisters are bound to be lauded as the RN's new 'look how great these are' ships;

2. Illustrious - same idea, 'look how great we are'

3. Implacable - "we're going ahead with our plans whether you like it or not"

and, I think my favourite for a peacetime ship...

4. Immaculate - let's face it, when not at war, sailors are kept busy by polishing, so she will be...

While not really a Royal Navy name, I have to admit that I like the idea of HMS International, so that you can have everything that could/does go wrong with these ships happen to it and have it pick up the informal name of "The International Incident"

She'd have to sail under the Red Ensign, rather than the White.

Edit - roachbeef beat me to it!

Last edited:

She'd have to sail under the Red Ensign, rather than the White.

Why would a Royal Navy ship sail as a British merchant ship?

Red Ensign - Wikipedia

Last edited:

Why would a Royal Navy ship sail as a British merchant ship?

Red Ensign - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

That sneaky royal navy, whats a better way to kill enemy merchant raiders then to dress your battleship up like a merchant!

The Deck-Armoured Battlecruiser

The Deck-Armoured Battlecruiser

Anyone could build a fast, well-armed, well-armoured ship on forty or fifty thousand tons, but to build one on 23,000 tons must surely mean that it would be a lesser vessel; a second-rate battleship, or a poorly armoured battlecruiser?

In 1924, few thought that it could be done. Even the men who did it, didn’t think that it was a certainty when they started their work. In classical terms, it wasn’t possible, but a combination of new technologies, new ideas and a willingness to accept that not everything on a ship had to be protected equally meant that it was shown to be achievable; with every accountant’s trick and sea-lawyer’s fiddle, there were literally tons to spare.

Design ‘1924-B/3’ had shown that a powerful ship could be built on 23,000 tons (particularly if the designers ‘cheated’ by planning to add up to 3,000 tons of improvements to torpedo protection and air-defence later). However, the weight of the four armoured turrets made it a marginal design.

In the New Year of 1925, two ideas came together. One was the concept of limiting the protection of a ship to a well-armoured citadel around the waterline, rather than trying to extend heavy armour far up the hull. The other was the consideration that damage to armament could be tolerated, providing such damage did not automatically result in the loss of the ship.

Both at the Battle of Stavanger and in other, smaller actions, ships had been lost due to progressive flooding, torpedo hits or (most probably) to shells penetrating and exploding inside their magazines. Providing there were adequate means to prevent fires spreading from turrets to magazines, a hit on a turret would not destroy a ship; it would merely reduce its fighting ability. If it were essential to save weight, it was therefore a legitimate design choice to reduce armour on areas other than magazines and accept the risk that turrets might be lost.

Associated with that was a new weight and labour-saving mechanism that had been proposed a few months earlier, by the armaments firm Vickers. They proposed simplifying (and lightening) the usual multi-stage system of below-deck handling rooms, shell bogies, lower hoists, turret handling rooms and upper hoists.

In their new system steps would be eliminated or combined, and more of the process would happen below the armour deck.

Deep in the ship, a series of ‘cages’ (one for each gun above) would be filled through flash-tight scuttles from the magazines, and by fixed rammers for the projectiles. The cages would be sitting on a combined hoist and turntable, which would then raise them up to the level of the armour deck while simultaneously turning them from the fore-aft loading position of the magazines until they matched the train angle of the turret above.

Unlike in traditional turrets, the heavy armour deck would extend through the barbette, and a central disk of this thick deck would turn with the turret. Once correctly orientated, the ‘cages’ would pass through holes in this deck, each of which was surrounded by a short armoured trunk . Now above the armoured citadel, the charges and shell would still be protected, as each cage would rise into a splinter-proof armoured hood which would be waiting for it. The cage would latch into the hood and the whole unit would then be lifted up, allowing flash-tight shutters to close the holes below as the hood rose out of the armoured trunk.

The cage and hood would rise all the way up to the gun by a traditional winch hoist, before shell and charge ramming took place as usual.

The amount of handling machinery was reduced, but there was no opportunity to arrange the shells and charges between upper and lower hoists. They therefore had to be inserted in the cage in the correct order, with the shell and the bottom and the charges on top. This meant the magazines would return to their pre-war position above the shellrooms.

The system eliminated the handling room below the turret and the shell bogies, saving considerable space and weight. However, it meant that all guns had to be loaded together, as the below-armour hoist and turntable would supply of all the turret’s hood/cage assemblies simultaneously.

If the magazines were safely isolated behind heavy armour, turret protection could be reduced.

However, one of the ship’s primary missions was to destroy cruisers, and it would be absurd if the main armament could be knocked out by a cruiser’s guns.

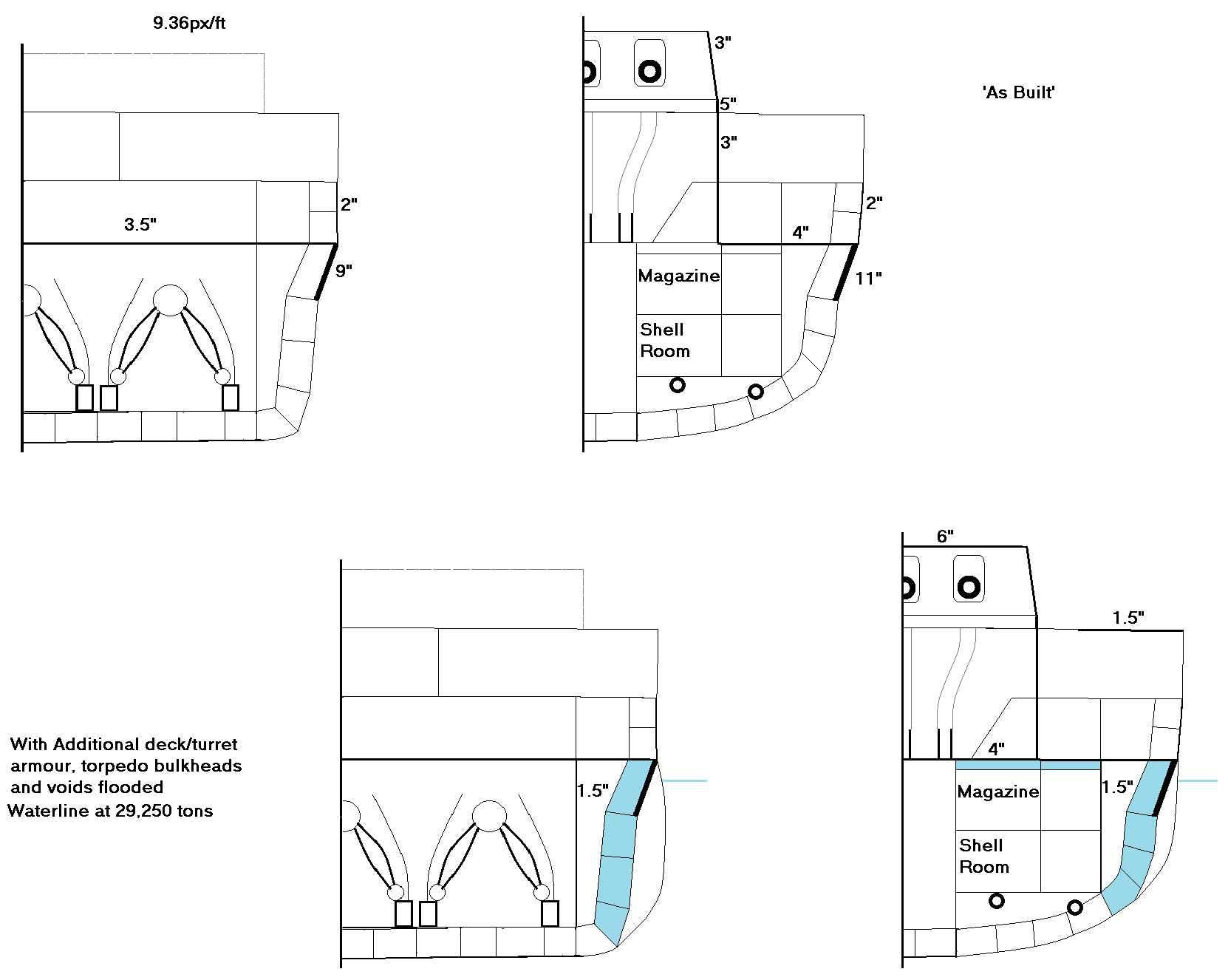

The three main turrets were therefore protected by a 7” faceplate, with 3” sides and rear, while barbettes would be 5” where exposed, reduced to 3” inside the hull. This would keep out 8” gunfire at practical battle ranges and would also be ample proof against splinters from larger shells. The only exceptions were the roofs of the turrets, which had only a ½” weatherproof plate ‘as designed’. A 5½” thick plate would later be added on top as part of permitted improvements in horizontal armour.

Away from the citadel, the ships were only ‘protected’, rather than armoured.

Above the armour deck the sides of the ship had 2” of protective plating over their 1” skin, in a similar fashion to a light cruiser. To improve resistance to flooding near the waterplane, the double hull also covered this space between the main and upper decks, and a thin layer of armour would be added to the edges of the foc'sle, justified as part of improvements to bomb protection.

Armour scheme, with and without improvements.

The ships were designed so that they would not be ‘inconvenienced’ by 8” fire, but they also had to be safe to fight battleships. The objective here was to ensure that battleships could be engaged at certain ranges, without the Captain having to concern himself over the immediate safety of his ship.

As the scouting force of a fleet, or in a pursuit action, or when trying to turn the head of an enemy line, the ships would engage enemy battleships at relatively long ranges. At these ranges, the deck presented a larger target than the shallow belt needed to protect the machinery and magazines, and was therefore of relatively high importance.

The machinery was armoured against 15” gunfire, with the 9” inclined belt capable of resisting the 1,920-lb shells at ranges above 19,000 yards, and the 3½” thick deck providing protection below 22,500 yards.

It was vital that the magazines be proofed against the heaviest gunfire, which the ships’ Chief Designer, Charles Coles, defined as the 2,340-lb shell that was fired at 2,450fps by the British 16” Mk.2 gun. Why he did not choose the higher-performance Mk.2* is something of a mystery, although there wouldn’t have been any weight to spare for any additional armour if he had.

An 11”, 20-degree inclined belt would defeat these shells above 17,500 yards, and a 4” deck would keep them out below 23,500. This heavier armour also covered the transmitting station and part of the aft engine room, partly to guard against the possibility of end-on fire reaching the magazines.

If the Captain were able to keep the ship at an angle to the enemy, those minimum ranges could be reduced, but the design objective was the ships could be ‘safely fought’ on any course at ranges around 20,000 yards.

Anyone could build a fast, well-armed, well-armoured ship on forty or fifty thousand tons, but to build one on 23,000 tons must surely mean that it would be a lesser vessel; a second-rate battleship, or a poorly armoured battlecruiser?

In 1924, few thought that it could be done. Even the men who did it, didn’t think that it was a certainty when they started their work. In classical terms, it wasn’t possible, but a combination of new technologies, new ideas and a willingness to accept that not everything on a ship had to be protected equally meant that it was shown to be achievable; with every accountant’s trick and sea-lawyer’s fiddle, there were literally tons to spare.

Design ‘1924-B/3’ had shown that a powerful ship could be built on 23,000 tons (particularly if the designers ‘cheated’ by planning to add up to 3,000 tons of improvements to torpedo protection and air-defence later). However, the weight of the four armoured turrets made it a marginal design.

In the New Year of 1925, two ideas came together. One was the concept of limiting the protection of a ship to a well-armoured citadel around the waterline, rather than trying to extend heavy armour far up the hull. The other was the consideration that damage to armament could be tolerated, providing such damage did not automatically result in the loss of the ship.

Both at the Battle of Stavanger and in other, smaller actions, ships had been lost due to progressive flooding, torpedo hits or (most probably) to shells penetrating and exploding inside their magazines. Providing there were adequate means to prevent fires spreading from turrets to magazines, a hit on a turret would not destroy a ship; it would merely reduce its fighting ability. If it were essential to save weight, it was therefore a legitimate design choice to reduce armour on areas other than magazines and accept the risk that turrets might be lost.

Associated with that was a new weight and labour-saving mechanism that had been proposed a few months earlier, by the armaments firm Vickers. They proposed simplifying (and lightening) the usual multi-stage system of below-deck handling rooms, shell bogies, lower hoists, turret handling rooms and upper hoists.

In their new system steps would be eliminated or combined, and more of the process would happen below the armour deck.

Deep in the ship, a series of ‘cages’ (one for each gun above) would be filled through flash-tight scuttles from the magazines, and by fixed rammers for the projectiles. The cages would be sitting on a combined hoist and turntable, which would then raise them up to the level of the armour deck while simultaneously turning them from the fore-aft loading position of the magazines until they matched the train angle of the turret above.

Unlike in traditional turrets, the heavy armour deck would extend through the barbette, and a central disk of this thick deck would turn with the turret. Once correctly orientated, the ‘cages’ would pass through holes in this deck, each of which was surrounded by a short armoured trunk . Now above the armoured citadel, the charges and shell would still be protected, as each cage would rise into a splinter-proof armoured hood which would be waiting for it. The cage would latch into the hood and the whole unit would then be lifted up, allowing flash-tight shutters to close the holes below as the hood rose out of the armoured trunk.

The cage and hood would rise all the way up to the gun by a traditional winch hoist, before shell and charge ramming took place as usual.

The amount of handling machinery was reduced, but there was no opportunity to arrange the shells and charges between upper and lower hoists. They therefore had to be inserted in the cage in the correct order, with the shell and the bottom and the charges on top. This meant the magazines would return to their pre-war position above the shellrooms.

The system eliminated the handling room below the turret and the shell bogies, saving considerable space and weight. However, it meant that all guns had to be loaded together, as the below-armour hoist and turntable would supply of all the turret’s hood/cage assemblies simultaneously.

If the magazines were safely isolated behind heavy armour, turret protection could be reduced.

However, one of the ship’s primary missions was to destroy cruisers, and it would be absurd if the main armament could be knocked out by a cruiser’s guns.

The three main turrets were therefore protected by a 7” faceplate, with 3” sides and rear, while barbettes would be 5” where exposed, reduced to 3” inside the hull. This would keep out 8” gunfire at practical battle ranges and would also be ample proof against splinters from larger shells. The only exceptions were the roofs of the turrets, which had only a ½” weatherproof plate ‘as designed’. A 5½” thick plate would later be added on top as part of permitted improvements in horizontal armour.

Away from the citadel, the ships were only ‘protected’, rather than armoured.

Above the armour deck the sides of the ship had 2” of protective plating over their 1” skin, in a similar fashion to a light cruiser. To improve resistance to flooding near the waterplane, the double hull also covered this space between the main and upper decks, and a thin layer of armour would be added to the edges of the foc'sle, justified as part of improvements to bomb protection.

Armour scheme, with and without improvements.

The ships were designed so that they would not be ‘inconvenienced’ by 8” fire, but they also had to be safe to fight battleships. The objective here was to ensure that battleships could be engaged at certain ranges, without the Captain having to concern himself over the immediate safety of his ship.

As the scouting force of a fleet, or in a pursuit action, or when trying to turn the head of an enemy line, the ships would engage enemy battleships at relatively long ranges. At these ranges, the deck presented a larger target than the shallow belt needed to protect the machinery and magazines, and was therefore of relatively high importance.

The machinery was armoured against 15” gunfire, with the 9” inclined belt capable of resisting the 1,920-lb shells at ranges above 19,000 yards, and the 3½” thick deck providing protection below 22,500 yards.

It was vital that the magazines be proofed against the heaviest gunfire, which the ships’ Chief Designer, Charles Coles, defined as the 2,340-lb shell that was fired at 2,450fps by the British 16” Mk.2 gun. Why he did not choose the higher-performance Mk.2* is something of a mystery, although there wouldn’t have been any weight to spare for any additional armour if he had.

An 11”, 20-degree inclined belt would defeat these shells above 17,500 yards, and a 4” deck would keep them out below 23,500. This heavier armour also covered the transmitting station and part of the aft engine room, partly to guard against the possibility of end-on fire reaching the magazines.

If the Captain were able to keep the ship at an angle to the enemy, those minimum ranges could be reduced, but the design objective was the ships could be ‘safely fought’ on any course at ranges around 20,000 yards.

Well that's an interesting scheme. Leaving your turrets vulnerable is brave but the shell handling system does seem to reduce the risk of a magazine explosion, how that will work in practice I'm not sure, it's easy to imagine that a near miss could jar the flash doors and then should a shell set off the charges in the hoist you'd lose the ship.

The main calibre is still unclear, the previous post said these ships have three turrets and your image suggests they have 3 gun turrets meaning 9 guns so even with this armour scheme I can't see how they could have the weight to carry 16" Mk.2*'s. If they are rules lawyering I'm guessing they've got an improved 13.5" built to the same standard as the 16" Mk.2* throwing a heavier shell at higher velocities and are getting around the treaty ban on new guns by claiming that this is simply an updated version of the BL 13.5" MkV made with modern manufacturing techniques, to do that they would have to stick with a 45 calibre barrel which is unfortunate but unavoidable. I wonder if they gave any consideration to copying R & R and going for a 6 guns of a larger calibre.

Still with that armament and assuming the armour scheme works this ship will definitely be able to destroy all of the other BCL designs and cause some damage to 1st rate battleships as they run away.

The main calibre is still unclear, the previous post said these ships have three turrets and your image suggests they have 3 gun turrets meaning 9 guns so even with this armour scheme I can't see how they could have the weight to carry 16" Mk.2*'s. If they are rules lawyering I'm guessing they've got an improved 13.5" built to the same standard as the 16" Mk.2* throwing a heavier shell at higher velocities and are getting around the treaty ban on new guns by claiming that this is simply an updated version of the BL 13.5" MkV made with modern manufacturing techniques, to do that they would have to stick with a 45 calibre barrel which is unfortunate but unavoidable. I wonder if they gave any consideration to copying R & R and going for a 6 guns of a larger calibre.

Still with that armament and assuming the armour scheme works this ship will definitely be able to destroy all of the other BCL designs and cause some damage to 1st rate battleships as they run away.

I don't think the British would feel comfortable settling for anything less than 15" guns, especially considering their requirement for the ship to be able to "safely fight" enemy capital ships at long range. Both the 1924-B/3 and 1924-C/2 designs mentioned earlier used 15" guns, and one of the main reasons brought up regarding the use of twin turrets over triples in the previously favored B3 was the extreme weight of the latter and the increased R&D cost. The idea to limit turret armor necessitates the latter, and removes the first problem entirely, thus the stigma against using triple 15" guns was likely alleviated. Then again, the 13.5" gun (especially if it is an improved version) would be more than enough to give cruiser captains around the world severe indigestion, as well as giving battleship and battlecruiser captains ample reason to worry.If they are rules lawyering I'm guessing they've got an improved 13.5" built to the same standard as the 16" Mk.2* throwing a heavier shell at higher velocities and are getting around the treaty ban on new guns by claiming that this is simply an updated version of the BL 13.5" MkV made with modern manufacturing techniques, to do that they would have to stick with a 45 calibre barrel which is unfortunate but unavoidable. I wonder if they gave any consideration to copying R & R and going for a 6 guns of a larger calibre.

Edit: I'm also pretty sure that this last update is missing a threadmark.

Last edited:

The need to fire all the weapons in a turret at once is going to play merry Hell with targeting. Surely that can be modified?

Expendable turrets? Meh. Never really bothered the cruisers in WW2.

I take that more as the need to reload all the guns at once not necessarily fire them all at once. you could fire one then another for ranging purposes but have to wait to reload them all.

The Deck-Armoured Battlecruiser

Well that's an interesting scheme. Leaving your turrets vulnerable is brave but the shell handling system does seem to reduce the risk of a magazine explosion, how that will work in practice I'm not sure, it's easy to imagine that a near miss could jar the flash doors and then should a shell set off the charges in the hoist you'd lose the ship.

The main calibre is still unclear, the previous post said these ships have three turrets and your image suggests they have 3 gun turrets meaning 9 guns so even with this armour scheme I can't see how they could have the weight to carry 16" Mk.2*'s. If they are rules lawyering I'm guessing they've got an improved 13.5" built to the same standard as the 16" Mk.2* throwing a heavier shell at higher velocities and are getting around the treaty ban on new guns by claiming that this is simply an updated version of the BL 13.5" MkV made with modern manufacturing techniques, to do that they would have to stick with a 45 calibre barrel which is unfortunate but unavoidable. I wonder if they gave any consideration to copying R & R and going for a 6 guns of a larger calibre.

Still with that armament and assuming the armour scheme works this ship will definitely be able to destroy all of the other BCL designs and cause some damage to 1st rate battleships as they run away.

The need to fire all the weapons in a turret at once is going to play merry Hell with targeting. Surely that can be modified?

Expendable turrets? Meh. Never really bothered the cruisers in WW2.

I don't think the British would feel comfortable settling for anything less than 15" guns, especially considering their requirement for the ship to be able to "safely fight" enemy capital ships at long range. Both the 1924-B/3 and 1924-C/2 designs mentioned earlier used 15" guns, and one of the main reasons brought up regarding the use of twin turrets over triples in the previously favored B3 was the extreme weight of the latter and the increased R&D cost. The idea to limit turret armor necessitates the latter, and removes the first problem entirely, thus the stigma against using triple 15" guns was likely alleviated. Then again, the 13.5" gun (especially if it is an improved version) would be more than enough to give cruiser captains around the world severe indigestion, as well as giving battleship and battlecruiser captains ample reason to worry.

Edit: I'm also pretty sure that this last update is missing a threadmark.

Well chaps there you have, a '23k tons' standard displacement battlecruiser reasonably protected by british standards but still fast and well arm, even if we don't know the calibre we could be sure that is not below 13,5" at least, I personally hope that this is the resources-saving ship that can be accepted by the Treasury and by that logic be persuaded to lend the money to build them in good numbers make up for the numbers of the fleet in general as well as to shore up the Empire's defences, but I still have confusion with the armor scheme of the image, in order to not make any wrong guessing, @sts-200 could you explain a bit more please?, and sorry to bother again.

Last edited:

Was this armoured shell hoist proposed OTL?

And a scheme of this new design, of course

I'm well aware these ships are built on a rather extremely low tonnage with presumably large guns however, the armor scheme itself is rather troubling. The very Nelson of our timeline inspired heavily protected yet short and low in the ship citadel is worrisome given how much of the armor is below the waterline. Underwater protection seems to be prayers and not much else, especially alongside the magazines. Seems like the upper belt and barbettes will be doing most of the major protective work in the long term, especially if they take on any more weight without proper mitigation. I guess that might just be something you need to live with shooting for such outrageous capabilities on such a low tonnage.

Only 4"? I hope they add more, else these boys will be tasting AP shells bombs quite a lot in WW2. That's less than armored CVs.

Just to note while a hit would be bad, Actually hitting a 30-knot or more LBC that is maneuvering is very difficult to do since as the Japanese constantly showed throughout WW2, a fast maneuverable ship can avoid a lot of bombs. And that also does not take into account the level of AA fire in the air. ( 30 knots seems a reasonable assumption as that is other nations LBC'S top speeds)

Edit: I just realized you're probably talking about ship fired AP rather than aerial bombing AP in which case, yeah they will take a lot of damage if they get hit. But even then it is still difficult to hit a maneuvering 30-knot ship, especially at long range and considering these things have been designed to hit enemy ships accuratly at up to 20,000 yards then I think they have a decent to a good chance of avoiding return fire.

Edit 2: Thinking over aerial attacks, can anyone tell me how well did mid to late 1920's British AA suites cope with late 1930's - early 1940's aircraft such as the Stuka or the B5N? Did it do enough to be considered a threat or was it more of a nuisance? Because I was just wondering if AA is limited by the Washington Naval treaty and therefore if aerial attack will be even more of a threat in this timeline.

Last edited:

Share: