The Dash for Home

Admiral Souchon could feel the vibration of the engines as the ship began to work up to full speed. Behind him, thick, black smoke belched from the two funnels, although it became almost instantly invisible against the dark western sky.

Since leaving Gibraltar six days earlier, his two ships had steamed far out into the Atlantic and kept well clear of the shipping lanes while he had decided on the best route home, in accordance with his orders. The Kaiser had given him discretion to attack enemy ships or land facilities in the event of war, but it was not until late on the fifth that he received radio signals telling him that Germany was now at war with Britain, and not just France as his previous information stated.

His plan to steam to conduct cruiser warfare for a few weeks against French shipping in the Atlantic was now far too risky. Although the number of British targets was immensely greater, so too were the number of Royal Navy warships that could hunt him down. He had therefore decided to return home. Pre-war plans for the replenishment of German Navy raiders were comprehensive, and his ships had been able to partially re-coal from a German merchantman far out at sea before they headed East.

Souchon knew he was taking a gamble either way. The route North towards Iceland, and across the foggy, storm-ridden Norwegian Sea might have been safer, but it was far longer. His ships would have to coal at least once more if they were to return home that way. Meeting a collier and then coaling at sea was a risky endeavour, while the route would mean passing through hundreds of miles of British-patrolled waters to the north of their homeland.

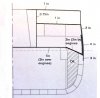

He had therefore chosen the other way for his largest and most valuable ship. It was much shorter, but it came within just a few miles of British bases. The Goeben was heading East, straight through the English Channel. He’d hedged his bet, by sending the Breslau via the northern route, where hopefully her smaller fuel needs could be more easily met, and where she might distract the enemy’s attention.

He looked North, where the dim glow of the pre-dawn light was fast overwhelming the dimmer glow of the lights of English coastal towns. If he chose to head that way, he thought, he could make his name and his ship’s name as famous as any in history. Attacking the home of the Royal Navy at dawn had a glorious appeal, but he knew it would be both futile and suicidal. Most of the British Fleet was far away to the North, and it was unlikely he would do much damaged before the shore defences of Portsmouth would either sink his ship, or cripple it, leaving him to be swarmed by light forces.

Instead, Goeben turned Northeast, heading for the Dover Strait and home. Two days ago, before they entered the busy shipping lanes leading towards the Channel, canvas had been stretched in front of the ship’s aft mast, creating a false funnel, and above the bridge, giving the ship a profile vaguely resembling a British Indefatigable-class battlecruiser. Yesterday, he had ordered the use of one of the oldest and simplest of ruses; at the ship’s stern, the White Ensign flew stiffly in the breeze.

He and the ship’s Captain had chosen the route and their timing to maximise the chance of surprise. Overnight, they had maintained a steady 18 knots, far below the ship’s top speed, allowing furnaces to be cleared in sequence ready for the day ahead. They’d been lucky too; at about midnight, they had passed right through the middle of a fishing fleet. The Chief Engineer reported that the port outboard shaft was now making peculiar noises, but they seemed to have escaped an ignominious end by having a net wrapped around their propellers.

Shortly after 0300, all of the furnaces had been lit and within the hour, Goeben had worked her way up to 24 knots, just as the period of Nautical Twilight dawned and her lookouts could give better warning of other vessels ahead. Fifty minutes later, as the day itself dawned, they were approaching the Dover Strait, and for the first time they were closer to the English coast than the French.

Admiral Souchon didn’t plan to merely sneak past the British.

Admiral Souchon could feel the vibration of the engines as the ship began to work up to full speed. Behind him, thick, black smoke belched from the two funnels, although it became almost instantly invisible against the dark western sky.

Since leaving Gibraltar six days earlier, his two ships had steamed far out into the Atlantic and kept well clear of the shipping lanes while he had decided on the best route home, in accordance with his orders. The Kaiser had given him discretion to attack enemy ships or land facilities in the event of war, but it was not until late on the fifth that he received radio signals telling him that Germany was now at war with Britain, and not just France as his previous information stated.

His plan to steam to conduct cruiser warfare for a few weeks against French shipping in the Atlantic was now far too risky. Although the number of British targets was immensely greater, so too were the number of Royal Navy warships that could hunt him down. He had therefore decided to return home. Pre-war plans for the replenishment of German Navy raiders were comprehensive, and his ships had been able to partially re-coal from a German merchantman far out at sea before they headed East.

Souchon knew he was taking a gamble either way. The route North towards Iceland, and across the foggy, storm-ridden Norwegian Sea might have been safer, but it was far longer. His ships would have to coal at least once more if they were to return home that way. Meeting a collier and then coaling at sea was a risky endeavour, while the route would mean passing through hundreds of miles of British-patrolled waters to the north of their homeland.

He had therefore chosen the other way for his largest and most valuable ship. It was much shorter, but it came within just a few miles of British bases. The Goeben was heading East, straight through the English Channel. He’d hedged his bet, by sending the Breslau via the northern route, where hopefully her smaller fuel needs could be more easily met, and where she might distract the enemy’s attention.

He looked North, where the dim glow of the pre-dawn light was fast overwhelming the dimmer glow of the lights of English coastal towns. If he chose to head that way, he thought, he could make his name and his ship’s name as famous as any in history. Attacking the home of the Royal Navy at dawn had a glorious appeal, but he knew it would be both futile and suicidal. Most of the British Fleet was far away to the North, and it was unlikely he would do much damaged before the shore defences of Portsmouth would either sink his ship, or cripple it, leaving him to be swarmed by light forces.

Instead, Goeben turned Northeast, heading for the Dover Strait and home. Two days ago, before they entered the busy shipping lanes leading towards the Channel, canvas had been stretched in front of the ship’s aft mast, creating a false funnel, and above the bridge, giving the ship a profile vaguely resembling a British Indefatigable-class battlecruiser. Yesterday, he had ordered the use of one of the oldest and simplest of ruses; at the ship’s stern, the White Ensign flew stiffly in the breeze.

He and the ship’s Captain had chosen the route and their timing to maximise the chance of surprise. Overnight, they had maintained a steady 18 knots, far below the ship’s top speed, allowing furnaces to be cleared in sequence ready for the day ahead. They’d been lucky too; at about midnight, they had passed right through the middle of a fishing fleet. The Chief Engineer reported that the port outboard shaft was now making peculiar noises, but they seemed to have escaped an ignominious end by having a net wrapped around their propellers.

Shortly after 0300, all of the furnaces had been lit and within the hour, Goeben had worked her way up to 24 knots, just as the period of Nautical Twilight dawned and her lookouts could give better warning of other vessels ahead. Fifty minutes later, as the day itself dawned, they were approaching the Dover Strait, and for the first time they were closer to the English coast than the French.

Admiral Souchon didn’t plan to merely sneak past the British.